Desktop Linux security is generally considered to be fundamentally more robust than Windows. However, that does not mean you can “install and forget” about your Linux desktop. It needs protection as much as any other operating system. In this article we’ll provide some practical advice on how to do that.

Getting started, a brief review of how Linux was conceived and developed will help with understanding why desktop Linux security is a more difficult nut to crack than some other desktop operating systems.

A brief history of Linux

In the early 90’s a Finnish University student named Linus Torvalds started work on a Unix-like kernel after being inspired by a scaled-down Unix-like operating system named MINIX. The kernel matured and eventually became the kernel for operating systems such as Android, ChromeOS and the desktop/server OS we refer to as Linux today.

Linux proper is only the operating system kernel which humans don’t interact with. Everything you’ve ever seen on a Linux machine is an application and not Linux, yet the name has prevailed to signify the entire operating system, much to the chagrin of Richard Stallman and The GNU (Gnu’s Not Unix) Project.

The GNU Project began when Torvalds was 14 years old, and 7 years before the Linux kernel was conceived. MIT alumnus Richard Stallman (RMS in hacker circles) recognized earlier on that in order for people to truly own their digital data, everything used to create that data, including the operating system and all its ancillary components, had to be non-proprietary. To that end RMS founded the GNU Project and wrote the first Free (as in non-proprietary) Software license known as the GNU General Public License in 1989. By 1991, the GNU project had created a number of utilities but still did not have a working kernel, which was dubbed the GNU Hurd. Torvald’s Linux kernel became a more viable alternative to the Hurd and because Torvald released it under the GNU General Public License, it became more expedient to combine it with the GNU utilities. Thus the first non-proprietary operating system came into being.

Background:

The word

Freein software circles refers to software that is not proprietary and can be used by anyone for any purpose. The distinction between the two possible meanings of the wordfreeare described with the phraseFree as in speech or free as in beer. In an attempt to make this distinction easier to convey, the termFree/Libre Open Source Software(F/LOSS, or FLOSS, sometimes just FOSS) was coined as a way to conflatefreeandliberty. In either case, the takeaway is the wordfreein this context refers to the fact that the software is non-proprietary, and free to use and modify.

The GNU Project maintains that today’s Linux

is really GNU software operating with a Linux kernel and should therefore rightfully be called GNU/Linux to ensure the GNU project gets proper credit for their tools. Sadly, humans have shown that they’re not likely to bother trying to wrap their tongues around the phrase GNU/Linux

so that battle is all but lost.

Back to Torvald’s kernel: MINIX was a bare-bones, educational operating system written by Andrew Tanenbaum as a teaching tool for his text book that Torvalds used at University. MINIX still exists today and is primarily aimed at low-resource embedded systems. Torvalds used that knowledge to create his own kernel and Linux was born.

Definitions

Kernel

Linux is a monolithic kernel. Without getting bogged down into the weeds, this essentially means that the kernel operates entirely in kernel space. A computer’s memory is made available in different ways. Memory that user applications can access is referred to as user space. Memory that only privileged processes such as those required by the operating system is available only to kernel space. This means that it is difficult for user applications to affect the operating system since the applications do not have access to the kernel’s processes.

Malware

Malware is the generic term for any type of software that does something bad. Viruses, Potentially Unwanted Programs (PUP), and Spyware are all examples of malware.

Spyware

Spyware attempts to steal sensitive information from your computer and transmit it to the bad guy. Popular methods of spying are keyloggers, which transmit every key you press, and browser trackers which track the sites you visit on the web.

Botnets

Botnets are RoBOT NETworks

which are used to launch Distributed Denial of Service (DDoS) attacks against websites. In order to bring down a target website, an attacker generally needs thousands, if not hundreds of thousands, of computers at his disposal. Since it’s not practical to actually own or rent that many computers, bad guys use your computer.

They do this by virtue of tricking you into installing their botnet code onto your computer, usually through standard phishing techniques. Once the botnet malware is installed on your system, it reports in to the bad guy, usually in an IRC channel and then goes to sleep. When the bad guy has enough bots ready to go, he issues commands to them and the bot on your computer, and many others, come to life and start sending abusive traffic at the targeted site. You, the user, remains blissfully unaware that your computer is being used in this way.

Viruses and Worms

A virus or a worm is a piece of malware that has the additional characteristic of being able to replicate itself. Most malware installs itself once, and if the bad guy wants to infect another computer he has to convince the owner of that computer to also install his malware and so on. By contrast, a virus or worm will install itself and then go looking for other network connected computers it can copy itself to.

The recent outbreaks of WannaCry and other ransomware attacks were worms. One person in the organization mistakenly clicked a phishing link and the worm was installed on their computer. It then went crawling through the network to find other computers and in a very short time every computer in the network was infected.

Ways in which Linux is more secure than Windows

Privileges by default

A very fundamental security principle is that of Least Privilege. This principle states that any entity, user or otherwise, should only be granted the minimum amount of privileges required to do its job and no more. For example, a user who only needs to create documents and print them does not also need the ability to change the screensaver or access the internet.

For multi-user operating systems, a second equally important principle is Isolation. The principle of isolation is employed in many ways. In this case, it is best used to describe user separation. One user’s activities should not be allowed to affect others, and data belonging to one user should be be accessible to another user unless specifically allowed.

Linux was built as a multi-user operating system from day one and therefore has these principles baked in. Windows was designed as a single-user desktop system and has had various functionality added to it over time to address the weaknesses of the original design in an internet connected world.

The more popular Linux distributions create a non-privileged user account for daily use whereas a desktop Windows user is typically an admin-level user. User Account Control (UAC) was introduced in Windows Vista to create more of a barrier to installation and requires users to specifically authorize certain actions by clicking an OK button when prompted.

By requiring administrator privileges to install programs, it is harder to deploy malware. However, the weakest link in any security chain is the user. While these privilege escalation tools are fully functional in the world now, many users will simply type in their administrator password, or click the OK button to allow highly privileged activities to occur whenever the prompt comes up. A large user base that does not have the knowledge to understand why they are being prompted to supply elevated credentials makes it very hard for these tools to be truly effective.

Adoption

There is much discussion as to whether a lower adoption rate of Linux attributes to being a smaller target for malware and therefore, less infections occur.

All malware is not created equal. Malware authors write their programs with some specific goal in mind. Many malware programs are used to recruit unsuspecting computers into becoming part of a botnet. Some malware is written to steal login credentials for sensitive sites. Some is written to simply wreck the computer it is installed on. In any of those cases, the malware author wants to be efficient. The goal is to write the code once and then deploy it repeatedly to as many different computers as possible. With that goal in mind, it is obvious that writing malware for Windows is a better goal than writing malware for Linux.

It’s virtually impossible to discover the true rate of Linux adoption. Part of the problem is that Linux is embedded is so many consumer devices that it’s not even clear how to count a device as a Linux device. The other major stumbling block is that desktop Linux is FLOSS software so there are no sales numbers that can be used. All we can really do is look at secondary data such as Linux downloads or ask people to register as Linux users. Different methodologies have put Linux desktop adoption anywhere between one and 34 percent, which is such a wide variation that it is all but useless. Some industry insiders note that the metrics in almost all studies are US-centric, so they do not reflect the global market share and may be as high as 12 percent worldwide.

What we do know, however, is that it is extremely unlikely that there are more Linux desktops in use than Windows desktops. As a malware author, it would make more sense to write Windows code as that will provide a wider attack base to work with.

Open Source

The Open Source software development methodology is the opposite of how software was typically developed in the past. Most software applications are created in-house and the source code is proprietary and hidden from anyone outside of the company. By contrast, Open Source software is just that – open. It is published in public code repositories to enable anyone to see the code, review it for bugs, and even modify it and contribute their changes back to the main project.

Open Source proponents use Linus’ Law to illustrate why it is the better development methodology.

given enough eyeballs, all bugs are shallow.

Open Source opponents use Robert Glass’ observation that since the number of bugs discovered in code does not scale linearly with the amount of reviewers, the law is a fallacy. There seems to be some merit to this. There are examples of open source projects that have bugs uncovered years after they were first introduced.

AppArmor

Application Armor is a kernel-level Mandatory Access Control (MAC) feature that restricts applications from accessing classes of computer resources. For example, AppArmor can allow a word processor to read and write files to the local hard drive, but deny it access the internet to send messages.

Recall that after writing the malware, the bad guys’ next hardest task is to trick people into deploying it on their systems. A common way to do this is to stick malware inside some completely different type of file, for example movie subtitle files. An application like AppArmor can be configured to disallow these files any write or internet capabilities since a subtitle file would have no need for those functions. In doing so, any malware in the file would be unable to copy itself or call home

as a newly recruited botnet member.

AppArmor was introduced into the Linux kernel 2.6.36 (Oct 2010) and first appeared in OpenSUSE Linux and is has been enabled by default in Ubuntu since 7.10. AppArmor likely does not need much tuning for a standard desktop system as its default settings are good enough to fend off most malware attempts. A deeper explanation of how AppArmor works and how it can be customized is on the Ubuntu wiki.

SELinux

Security Enhanced Linux is another MAC system that precedes AppArmor by several years. The United States National Security Agency (NSA) created SELinux as a series of kernel patches and user space tools. It was first included in the 2.6.0 test version of the Linux kernel (2003).

Most desktop users find SELinux complicated to configure, and it also requires a file system that supports labels whereas AppArmor doesn’t care about the type of file system. For those reasons, AppArmor has take over as the predominant MAC system for desktop Linux systems.

How to protect your Linux machine

Antivirus

There are some articles on the internet that claim antivirus is just not needed on a Linux desktop. This short-sighted view of the world helps the spread of malware. Every computer connected to the internet is participating in that network and has the ability to receive malicious files. It costs nothing, literally, to run antivirus on Linux, so it’s a mystery why some writers feel that not using Linux antivirus is worth the risk. There is ample evidence of Linux malware in existence.

It is important to run antivirus on a Linux machine even if you feel you’re not at risk of being infected. Most Linux desktops are part of a home or office network that also includes Windows computers. Although it is unlikely that a Linux machine could be infected by a Windows virus, it can easily transport the malware to the Windows machines. To make matters worse, Linux servers are frequently used as file servers or mail servers in office environments which means they are constantly exchanging files with the other computers in the office. A malicious file stored on a Linux machine that’s being served out to Windows workstations is a bad thing that antivirus will help detect.

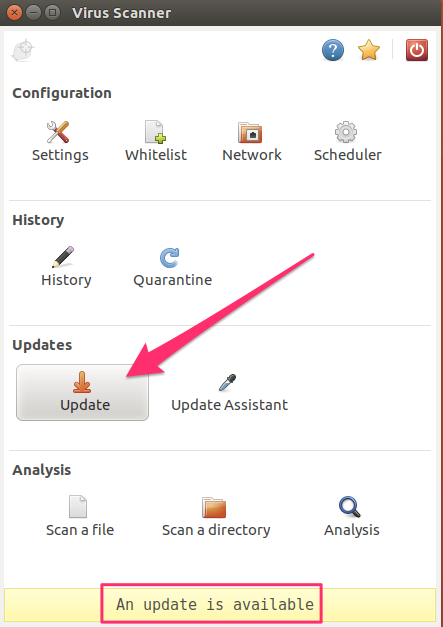

ClamAV is a common F/LOSS antivirus application that can be installed easily from the Ubuntu repositories. The article I’ve linked to has detailed instructions how to install and configure ClamAV.

Installing it on a Debian strain such as Debian itself, or any of the Ubuntu variants is usually as simple as using apt-get.

sudo apt-get update && sudo apt-get install clamav clamtkThat command should install clamav, freshclam (the signature updater), and the graphical user interface (clamtk). You’ll want to update ClamAV right after installation to make sure you have the most current signatures. That can be done from the settings panel in the ClamTK user interface.

Or you can do it from the command line using the freshclam command.

$ sudo freshclam

ClamAV update process started at Sun Jul 16 08:58:18 2017

main.cld is up to date (version: 58, sigs: 4566249, f-level: 60, builder: sigmgr)

daily.cld is up to date (version: 23568, sigs: 1740160, f-level: 63, builder: neo)

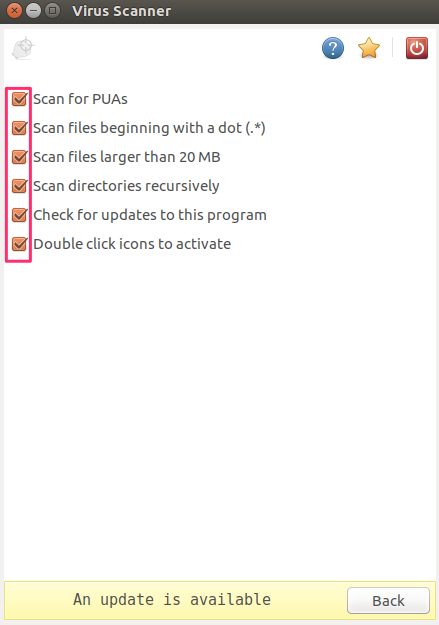

bytecode.cld is up to date (version: 306, sigs: 65, f-level: 63, builder: raynman)Next, ensure ClamAV will scan for every type of malware in the Settings option.

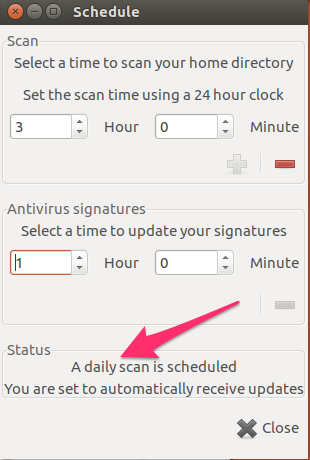

Finally, it makes sense to set up a scanning schedule which can also be done from the Scheduler panel.

ClamAV can be installed in Redhat Packagmage Manager (RPM)-based distros using yum or the distro-specific package manager.

sudo yum install clamav clamdRootkits

Rootkits are another danger, and anti-virus programs can be unable to detect them. Because a virus can only really infect a system if it is run by a root or administrator user, a common attack vector for Linux is to trick the user into installing one of these rootkits. A rootkit is a piece of malware that is able to obtain root-level permissions on a Linux box without the user knowing it. Rootkits are generally bundled in with other, legitimate looking, software that tricks the user into becoming root for installation. At that time, the rootkit also installs and since the installation was done as the root user, the rootkit now has root permissions as well. Rootkits are very hard to detect because they have the ability to alter any file on the system which means they are able to cover their tracks. Some bad guys are sloppy, though, and scanning for rootkits using app like chkrootkit can sometimes uncover it. If your system has been infected with a rootkit, your best course of action is to assume the entire system has been compromised and format it. You should also be wary of installing any applications from a backup after reinstalling your system if you’re not able to determine where the rootkit came from in the first place. You may end up re-installing the rootkit.

Chkrootkit can be installed from the Ubuntu repositories using apt-get.

$ sudo apt-get install chkrootkitThe congruent command in an RPM based system is:

$ sudo yum install chkrootkitTo see the tests that ckrootkit can perform, use the -l (L) switch:

$ chkrootkit -l

/usr/sbin/chkrootkit: tests: aliens asp bindshell lkm rexedcs sniffer w55808 wted scalper slapper z2 chkutmp OSX_RSPLUG amd basename biff chfn chsh cron crontab date du dirname echo egrep env find fingerd gpm grep hdparm su ifconfig inetd inetdconf identd init killall ldsopreload login ls lsof mail mingetty netstat named passwd pidof pop2 pop3 ps pstree rpcinfo rlogind rshd slogin sendmail sshd syslogd tar tcpd tcpdump top telnetd timed traceroute vdir w writeThe command sudo chkrootkit can be run without any options which will run all of the tests. There is a lot of output from this type of check. The criticality of each result is in the right-hand column and can range from Possible rootkit

to suspicious files

to nothing found

.

Sarching for Linux/Ebury - Operation Windigo ssh... Possible Linux/Ebury - Operation Windigo installetd

Searching for 64-bit Linux Rootkit ... nothing found

Searching for suspicious files and dirs, it may take a while... The following suspicious files and directories were found:

/usr/lib/python3/dist-packages/PyQt4/uic/widget-plugins/.noinit

Checking `chfn'... not infected

A competent systems administrator will need to assess these messages. Rootkits are, by their nature, very hard to detect so chkrootkit can usually only let you know when it sees something not quite right. A sysadmin will need to investigate each case to determine if there is an actual risk or if it is a false positive.

Tripwire

It’s hard to have a discussion about Linux security without Tripwire coming up. Tripwire is a host based intrusion detection system

. That just means it is installed on a host (computer) instead of a network, and it can detect if files have been changed by an intruder.

I only mention it in this article to point out that Tripwire is intended for use on servers, not desktops. It’s probably theoretically possible to install it on a desktop, though that is not its intended purpose.

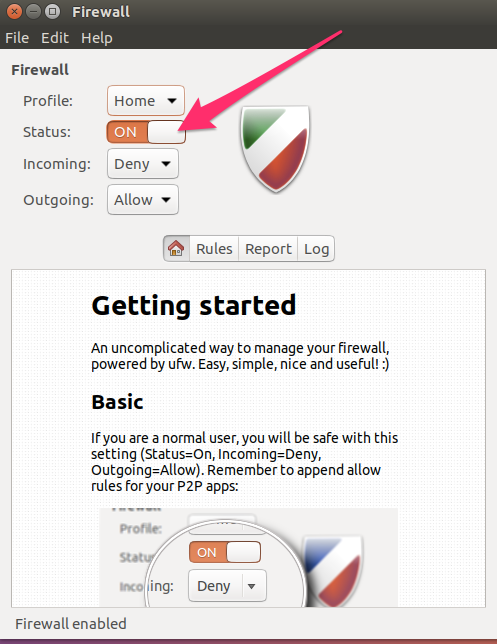

Firewall

We’ve all become familiar with the word firewall by now, but it may not be clear what it does. A real, physical firewall is a fire resistant wall that stops a fire in one room from spreading to another room. Real firewalls are common in office buildings and apartment complexes. Taking that concept to the internet, a firewall is software that prevents traffic from one segment of the network from coming into another segment. Specifically, it stops traffic from the internet coming in to your home network unless specifically requested.

Most houses probably have a router these days and the router performs some of the basic firewall functionality. A router should not come configured to accept incoming connections at all, but it’s best to always check the router instructions to be sure. A good double-check for open incoming ports is Gibson Research’s Shield’s Up! port checker.

Ubuntu variants come with the Ultimate Firewall (UFW) installed, or in the repositories. To see if it is installed type ufw at the command line. If you get something like $ ufw then it is installed. If it’s not installed, apt-get will do that for you. Optionally, install gufw if you want the graphical user interface to configure UFW, although it is extremely easy to handle just from the shell.

ERROR: not enough args

$ sudo apt-get install ufw gufwUFW will not activate after installation.

$ sudo ufw status

Status: inactiveYou’ll need to make a rule or two first, then you can activate it. To allow only my IP access via SSH, the command looks like this (use your own IP, not 11.22.33.44):

$ sudo ufw allow proto tcp from 11.22.33.44 to any port 2222To check if it took, use status:

$ sudo ufw status

Status: active

To Action From

-- ------ ----

2222 ALLOW 11.22.33.44To remove a rule, it’s easiest to do it by number. Run status with that number option and then delete that number rule:

$ sudo ufw status numbered

Status: active

To Action From

-- ------ ----

[1] 2222 ALLOW IN 11.22.33.44$ sudo ufw delete 1

Deleting:

allow from 11.22.33.44 to any port 2222 proto tcp

Proceed with operation (y|n)?To activate the firewall, use enable:

$ sudo ufw enable

Command may disrupt existing ssh connections. Proceed with operation (y|n)? y

Firewall is active and enabled on system startupTo disable it, use disable:

$ sudo ufw disable

Firewall stopped and disabled on system startupUFW is really just a front-end for IPTables as you can see if you run sudo iptables -L when UFW is enabled. There are many front ends to IPTables, or IPTables can be used directly, but UFW makes it very easy.

The graphical UI allows all the same functions.

Updates

Some of the most easily exploitable attack vectors in any software are known weaknesses. In hacker parlance, the term [zero day exploit](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Zero-day_(computing) (or just 0-day

) refers to an exploit that has been discovered but is not yet known by the software vendor. In effect, this gives the vendor zero days

to fix it once they become aware of it. This means that zero-days are the most dangerous of all exploits because the bad guys are actively exploiting it while the vendor is racing to patch it. Sooner or later, the vendor will patch it and issue an update for their product which closes that exploit.

When the vendor issues the patch, the vulnerability will become very widely known. Other bad guys who did not know about the vulnerability yet can download the update and analyze it. In many cases they are able to discover what the exploit was based on what has been changed in the update. They can then use this information to go hunting for instances of this application which have not yet been updated.

You can infer from this that waiting to update software on your computer simply leaves your system open to a longer period of time when it can be successfully attacked. It is important to apply updates, at least security updates to your system, as soon as practical after they become available.

As an extremely graphic example of the danger of 0-days, the recent WannaCry ransomware attack that infected more than a quarter-million computers in over 150 countries used a 0-day exploit in Microsoft Windows Server Message Block (SMB) protocol named EternalBlue

. In this case, EternalBlue was not new; it is generally agreed that it had been discovered by the US National Security Agency years ago. Instead of informing Microsoft of the vulnerability at the time, the NSA kept quiet about it and used it to attack computers worldwide for years. The NSA only disclosed the vulnerability to Microsoft after the exploit was stolen from them by the hacker group The Shadow Brokers and published to the world.

Internet

The internet is the most efficient delivery system of malware ever conceived by humans. Anyone, anywhere can send malware to you via common everyday methods such as email. If you fall for it and install the malware, then your computer can start sending data to the bad guy over the internet right away. In the case of ransomware, it would become fairly obvious pretty quickly that your computer had become infected. However, if the malware is designed to recruit your computer into a botnet, or silently log all your usernames and passwords, you may never notice it is installed unless you’re using antivirus and malware protection.

It can be hard for a bad guy to get through firewalls, routers, and antivirus. It’s easier to attack from the inside by tricking you into running programs. While many of us are becoming savvy to phishing emails, it is much harder to detect drive-by download attacks. Drive-by attacks refer to sites that download malicious Javascript or other executable content to your browser without you knowing about it. Of the many ways to do this, Javascript and Flash, are the worst offenders.

Javascript

Surfing the web with Javascript enabled is inviting attack. There are many who will say that the internet is totally broken without Javacript and therefore it’s not practical to turn it off, but that is not true. Using a plugin like ScriptBlock for Chrome or NoScript for Firefox will allow you one-click access to enabling Javascript for sites that need it. The default position is to disable Javascript and then enable it on a site-by-site basis. This means that future visits to sites you’ve already trusted will be allowed to run Javascript.

Flash

Adobe Flash is so dangerous that I wrote an entire acticle on the subject of Flash vulnerabilities. Flash has one of the highest critical vulnerability rates of any piece of software I’m aware of.

NoScript for Firefox blocks Flash as well as Javascript, and Chrome has Flash turned off by default. You’ll have to go out of your way into http://chrome/settings/content to enable Flash in Chrome. If you need to do so, you can use a plugin like Flashcontrol to control what sites are allowed to execute Flash.

Virtual Private Networks (VPNs)

VPNs are a standard security layer which most security and privacy conscious people are aware of. A Linux desktop is just another internet-connected machine and as such, has no special protections against network snooping. Therefore, using a VPN on a Linux machine is just as essential as using a VPN with any other operating system.

When using a VPN, network traffic that leaves your desktop is encrypted and is not decrypted until it reaches the VPN server that you’re using. Incoming traffic is encrypted at the VPN server and only decrypted when it arrives on your machine. That means you are protected somewhat against snooping by your ISP. If you’re in a situation where you’re using an untrusted network, such as public wifi, then a VPN is essential as that encryption will prevent bad guys on that same network from being able to read your packets.

There is growing support for VPNs that support Linux these days. If you’re somewhat tech-savvy, you can opt to build your own VPN server using an Amazon EC2 instance. If you’d rather just have something that works out of the box, Comparitech maintains a list of Linux VPN providers here.

OpenVPN is the most common VPN protocol on Linux and many of the vendor offerings actually use OpenVPN under the hood. OpenVPN is popular because it uses the trusted SSL protocol, can operate on any port, and supports Perfect Forward Secrecy. If you’re using a vendor supplied VPN, look for one that uses OpenVPN.

Download integrity

Phishing emails generally try to get you to do one of two things: trick you into logging in to a fake site so the bad guy can steal your username and password, or trick you into installing some software onto your system that will benefit the bad guy in some way. As the effectiveness of phishing emails drops, bad guys have to find other ways to trick us. One of those ways is to make their malware look like good software and we install it on purpose.

Malware extensions will usually install ads on your system or redirect your searches to some revenue-generating search engine, or they will install other applications that you don’t want along with the extension you do want. This practice is so widespread now that bad guys are purchasing abandoned extensions with good ratings and injecting malware into them. This is more effective than developing a new add-on because new add-ons start with no ratings and are subject to a higher level of scrutiny by the browser’s add-on stores.

Source of the download

It is important to be wary of exactly what you’re downloading and where you’re downloading it from. For example, downloading an antivirus program from the vendor’s legitimate website is probably OK. Downloading it from some third-party website with a domain name that doesn’t seem to be related to the vendor is probably not OK. This also applies to Linux distribution repositories, which are covered later in this article.

File checksums

Some applications aren’t really conducive to being downloaded from a single spot such as a vendor’s website. Many applications, especially security and privacy applications, are distributed over other methods like torrents. Without a single identifiable download source, it is harder to determine if you can fully trust the application. One method that some software authors use is to provide a mathematical checksum of their application. Users can then run the same mathematical function against the file they downloaded and if the two sums match, then it is likely that the file has not been altered.

MD5

While MD5 has been fairly soundly deprecated as a reliable checksum, it is still in wide use. Using chkrootkit as an example, I see that the MD5 signature for the zip file is published on the chkrootkit site as a6d7851f76c79b29b053dc9d93e0a4b0. I should be able to trust that since it comes direct from a link on the official chkrootkit site.

I then get a copy of the same zip file from a torrent, or some other source, and run md5sum against my newly downloaded file:

$ md5sum chkrootkit-m.zip

a6d7851f76c79b29b053dc9d93e0a4b0 chkrootkit-m.zipSince the checksums match, that is a reasonable assurance that the file has not been accidentally corrupted. But, due to weaknesses in the MD5 algorithm, it can’t be an assurance that the file has not been intentionally changed and crafted in such a way as to ensure the MD5 checksum does not change.

The same process with a stronger algorithm will provide a higher level of confidence that the download has not been altered. Using the SHA256 signature against an OpenOffice download is one example. The OpenOffice SHA256 signature is on the OpenOffice download page”

f54cbd0908bd918aa42d03b62c97bfea485070196d1ad1fe27af892da1761824 Apache_OpenOffice_4.1.3_Linux_x86_install-deb_en-GB.tar.gzI need both the SHA256 checksum file as well as my download of the same name to make this work:

$ ls -l Apache_OpenOffice*

-rw-rw-r-- 1 xxx xxx 145578419 Jul 16 10:11 Apache_OpenOffice_4.1.3_Linux_x86_install-deb_en-GB.tar.gz

-rw-rw-r-- 1 xxx xxx 125 Jul 16 10:11 Apache_OpenOffice_4.1.3_Linux_x86_install-deb_en-GB.tar.gz.sha256

$

$ sha256sum -c Apache_OpenOffice_4.1.3_Linux_x86_install-deb_en-GB.tar.gz.sha256

Apache_OpenOffice_4.1.3_Linux_x86_install-deb_en-GB.tar.gz: OKThe OK

at the end of the last line means that the tar.gz file’s SHA256 checksum matches.

Trusted repos

The first installation path for most Linux users is the distribution repositories. Using tools like yum or apt-get is a convenient way to install software that is known to be compatible with your particular distro. Those repos are audited and vetted by the distribution maintainers so there’s a fairly high level of confidence that applications in the repos are safe. While it may turn out that an application has some inherent flaw down the road, it would be difficult for someone to maliciously change an application in a repo and get that change past the gatekeepers.

Having said that, there are many unofficial repos and those are not guarded at all. In Ubuntu, a software repo can be added by using apt-get and the name of the Personal Package Archive (PPA) like so and replacing REPOSITORY_NAME with the applicable repo.

sudo apt-add-repository ppa:REPOSITORY_NAMENote that you must use the sudo command to add a repository. This is a sign that by doing so, you’re trusting the software in that PPA. You’ll also be using sudo to install software from that PPA when the time comes, so it is important to be sure you trust it.

Many PPAs are provided by Ubuntu developers as a way to offer more current software that has not been included in Ubuntu, or to provide software that is not included in Ubuntu at all. However, you’re essentially installing software from an unknown source so the same precautions as downloading from a website should be considered.

Opsec

Operational Security (OpSec) practices are no different in Linux than with any other operating system. OpSec is a practice an adversary can use to collect large amounts of seemingly trivial and unrelated information about you, and then put it all together to do some very non-trivial and damaging thing. Classic examples are trying to use social engineering techniques to gain password recovery information such as mother’s maiden names and names of first pets, then using that information to break into an Amazon or Apple account. From there, birth dates, mailing addresses and possibly some credit card information can be gained which allows for a further escalation of the attack to an even more important level such as bank transfers.

Important day-to-day OpSec considerations are things like:

- Do not reuse passwords across sites. Over 50 million accounts have been hacked and sold since Have I Been Pwned started out. Those dumps are gold to bad guys because they know that many of those username and password combinations will work on many sites.

- Use two-factor authentication where available. Two-factor authentication (2FA) means that you have to provide two types of authentication in order to log in to your account. The first is usually your password. The second is usually a numeric code that is provided by an authenticator application like Google Authenticator, or is sent via SMS text message to your phone. The numeric codes change, usually every minute, or on each use. The security advantage here is that if a bad guy was able to obtain your username and password, it would still be impossible to log in to your account without that 2FA code as well. Only a small number of websites support 2FA at this time, but you should enable it wherever possible.

- Seek to avoid the publication of personal information such as your address or birthdate online. Address information is usually fairly easy to find because so many organizations publish things like member lists, or donation records.

- Encryption: At the very least, use disk encryption and ensure your computer is shut down when you’re not using it. That will encrypt your hard drive so even if it is stolen, it will be hard to recover data from it. At higher levels, employ file encryption for your more sensitive files so that they are encrypted even when the computer is running or on standby.

- Use a password manager. Following rule #1 (do not reuse passwords) is almost impossible without the use of a password manager. The number of passwords needed to navigate today’s internet will quickly exceed anyone’s ability to manually manage them. In addition, most password managers have a notes function. This is useful because there’s no reason to use the actual real answers to password recovery questions. Making up false answers and then storing them as notes in your password manager can foil bad guys even if they have managed to obtain the correct answers.

In closing, security is a 24/7 job. There is no point where you will have implemented enough security and you will be done

securing your computer. Following the basics I’ve laid out here will make you high hanging fruit

and harder for casual hackers to penetrate. Threats evolve daily, however, and you may need to change practices to keep up. It’s also best to plan ahead. Consider what you will do when you are hacked, not if you are hacked. A little preparation can make that day a lot less stressful.

Very insightful! Your article helped me when trying out Ubuntu for the first time when I’m used to Windows.

Massive thanks for the article,well written ,easy to follow guides helps to put new users mind at rest Thanks again.