Unless you’ve been a victim of adware, you probably never paid it much attention. But when you dive into the topic and all of its nuances, it actually turns out to be a lot more complex than it seems on the surface.

To appreciate its scope, let’s start by considering the definition of adware given by various authorities. Merriam-Webster keeps things simple, describing adware as:

computer software that is provided usually for free but contains advertisements.

Merriam-Webster is pretty reliable in most of its definitions, but you could argue that it may not be the best source when it comes to tech matters. If we turn to Techopedia, we get:

Adware is free computer software that contains commercial advertisements. Adware programs include games, desktop toolbars or utilities. Commonly, adware is Web-based and collects Web browser data to target advertisements, especially pop-ups.

This is pretty broad, so let’s look at some organizations that are more focused on adware-related topics. Heimdal Security gives us:

Adware is a type of malicious software (or malware, for short) that quietly collects information about you, such as browsing history and search results, while at the same time feeding you ads, and it does all of this without asking for your consent.

On the other hand, Kaspersky gives us this:

Adware is the name given to programs that are designed to display advertisements on your computer, redirect your search requests to advertising websites and collect marketing-type data about you – for example, the types of websites that you visit – so that customised adverts can be displayed.

As you may have noticed, our article is already off to a bad start. There are significant differences between these four definitions.

Under the definitions of Merriam-Webster or Techopedia, you could include a significant amount of the software that we use today, including Facebook and many of Google’s offerings.

Heimdal Security is more restrictive, deeming that the software must be malicious. Google’s services and Facebook don’t really cause damage to your systems, so this rules them out.

However, the other half of the definition seems to fit them like a glove “…collects information about you, such as browsing history and search results, while at the same time feeding you ads, and it does all of this without asking for your consent.” To be fair to Facebook and Google, they have gotten significantly better at asking for consent and giving granular control to users in the last couple of years, but there’s still lots of room for improvement.

While Kaspersky’s initial definition isn’t so clear, the article it is drawn from mainly refers to unwanted applications or programs that tend to be unintentionally downloaded by the user. These programs then display intrusive ads that often hamper the user’s experience, and may also be involved in collecting user data.

When you look up most articles concerning adware, this is usually the kind of thing they refer to as adware – either apps or programs that are directly downloaded to computers or mobile devices. This could be because most articles on the subject were written by security organizations, and this kind of harmful adware is what falls into their domain.

See also:

Does the common understanding of adware make sense?

This article will tread a different path. While adware can be seen as a negative term, when you examine it in-depth, there isn’t a clear line between what constitutes malicious adware and what we would consider ad-supported software, like Facebook and Google.

Instead, the contention is that adware is a spectrum that ranges from:

- Legitimate software that is free for users. To sustain its development, it is funded by ads.

- Malicious software that offers no benefit to users. It displays annoying ads and may spy on users without giving anything in return.

As we will discuss later in the piece, you will see that most forms of ad-supported software and malicious adware fall somewhere in between these two extremes.

Perhaps in earlier times, it was easier to make a clear distinction between the two. However, in the current tech climate, numerous examples show there is no obvious line. Instead, it is more of a gradient, with various developers engaging in somewhat dubious practices, slowly sliding down into the depths of what is clearly malicious.

Adware is a mixture of advertising and software, so throughout the article, we will be discussing various examples along the line of where the two fields intersect. This will show just how gray the area is between ad-supported software and adware under its traditional definition.

We will start by discussing legitimate ad-supported software, then move on to talk about behaviors that are more damaging to users. The reasoning behind this is that it would be ludicrous to warn readers of the intrusive ads and spying practices of traditional adware without also highlighting very similar practices employed by software that many of us rely on each day.

After covering the various forms of ad-supported software, we will move on and talk about it in its most malicious forms, as well as how you can prevent or remove it.

See also: What is Malvertising?

Adware as ad-supported software

To start, let’s be clear: ad-supported software is important. This article has no intention to harm or detract from software that is free for users in exchange for displaying ads to them. As long as certain conditions are met, it can be just as valid of a funding model as paid software, freemium software, or software that sustains its development through donations.

What is ad-supported software?

Ad-supported software is simply software that uses advertising to either totally or partially fund its development. Good software is often complex. Not only does it need highly skilled people behind it, but it also takes a lot of time.

It’s not something you can just build and forget about either – it needs to be updated with new features to appease users and to continue its compatibility with the rest of our tech ecosystem. When security vulnerabilities are discovered, these also need to be patched in a hurry, otherwise everyone who uses the software is endangered.

In the past, these expenses were generally covered by selling the software. In the last decade or two, people seem to have become accustomed to getting many of our online software and services for free, so a significant proportion of the software industry has moved its funding model to cater to them.

One of the most popular business models is now ad-supported software, where developers cover their costs – and hopefully make a neat profit – by selling space in the interfaces of their software to advertisers. Some of the best examples of this are YouTube or Facebook, which display ads before videos and in the News Feed (among other places), respectively.

Advertisers are generally happy to pay them a little each time their ads are shown, in the hopes of attracting sales or further brand awareness. Advertisers generally either pay the developer each time someone clicks on an ad, or whenever an ad is displayed to a user.

The ad-supported model can make the developers happy, the advertisers happy, and the users happy as well. In many cases, users get to use sophisticated software without having to pay a cent.

While there are some issues that come alongside the ad-supported model, it’s hard to deny its benefits. It’s particularly useful for those without much disposable income because it allows them to access services that they may otherwise be excluded from.

It’s also convenient for software that individuals rarely use – it doesn’t make much financial sense to pay a lump sum or a monthly subscription fee for something that you may only use once or twice each year. Most of us don’t mind looking at a couple of ads if it can save us a reasonable amount of money.

Advertising-supported software in its ideal form

As we stated above, there’s nothing objectively wrong with giving people the option to use a free service that supports itself with ads. However, we should lay out some conditions for what we would consider an ideal ad-supported business model, at least from the users’ perspective:

- The software should be built by developers with a good reputation who can be trusted.

- Any ads should be vetted and closely monitored to protect users from danger. This could include screening unsavory ads away from children, and removing any malicious ads that could infect users with various types of malware.

- The ads shouldn’t take up an unreasonable amount of screen space or be too intrusive for users.

- The software should only be downloaded when the user does so intentionally. It should not be secretly bundled with other software or use even more devious means to install itself.

- The software should only perform the tasks that it clearly specifies. There should not be anything hidden occurring in the background, whether it be installing other software or spying.

- Any licensing agreement should be simple and easy to read. Unexpected elements should not be hidden in legalese.

- If the developers ever make important changes, they should notify their users of what has been done, and any potential ramifications.

- Any potential privacy compromises should be opt-in, rather than opt-out. Privacy settings should be easy to understand, and users should have control over what information they share.

It’s a pretty long list, but these are all reasonable requests. Unfortunately, we have to come crashing back to earth. Realistically speaking, most of the commonly used ad-supported software doesn’t reach these lofty ideals.

Some might make small and understandable compromises, while others veer so far away into harmful territory that they seem little better than malicious adware.

The reality is that following many of the above points would leave a lot of money on the table, and either economic pressures like competition, or perhaps simple greed, drive developers in a different direction.

Examples of ad-supported software

Let’s start our journey into the world of adware by looking at examples of ad-supported software that would almost never be referred to as adware in the traditional sense.

We will begin by discussing ad-supported software that is purposely downloaded by users to accomplish certain tasks and has few drawbacks apart from the fact that it displays ads.

Afterward, we will discuss other kinds of software that aren’t generally considered adware – either because we are so accustomed to them, or because they are web-applications that aren’t installed locally on our systems.

We will delve into how these differ from standard definitions of adware, but still have enough of an overlap to merit their inclusion. Finally, we will get to the really nasty stuff, the undisputable adware. We’ll tell you how to recognize the telltale signs of an adware infection, how to avoid it in the first place, and how to remove it if it’s running on your system.

The Brave browser

The Brave browser is one of the better examples of software that aligns with most of our above-mentioned ideals, but it’s not perfect, and it hasn’t avoided controversy either. It’s a little complicated, but the Brave browser is essentially a privacy-focused web browser that offers an alternative to the likes of Chrome and Firefox.

Its CEO and co-founder is Brendan Eich, who is renowned in the tech sphere as the creator of JavaScript and as the co-founder of Mozilla. Without moving into the realm of hyperbole, there aren’t many in tech with such an impressive resume.

According to Brave’s website, it has a comprehensive vetting process for ads. Potential advertisers have to go through an approval process that begins with a request form that is used to select those who are allowed to be put on the waitlist. Individual ads are also approved by real people before being added to the ad server.

There don’t seem to be any publicly available figures about the rates of malicious ads displayed through the Brave browser versus other ad networks, but its vetting process appears to be as, or more, thorough than others in the online advertising domain.

The Brave browser has attracted criticism because it blocks the ads displayed on websites by default. Instead, it offers users ads from its own network. This setup gives Brave users far more control over their browsing experience. They can opt-in to receive ads, making a small amount of money for the ads that they view.

The control it gives users allows them to configure ads in a way they find appropriate. This stops the ads from feeling too overwhelming or intrusive.

When publishers partner with Brave, they also receive a portion of this advertising revenue. The Brave platform also allows users to easily make donations to their favorite websites and content providers.

Whether Brave’s approach to advertising is good or bad depends on where you sit in the equation. Site-owners have a legitimate reason to be mad, because their ads are blocked, meaning that unless they are Brave partners, they miss out on revenue from site visitors that use the Brave browsers.

At the same time, many websites have been known to host malicious ads, so security-conscious users also have legitimate reasons to block them.

Brave doesn’t secretly download itself onto the devices of its users, and the company has a commendable approach to transparency and privacy. The company is relatively upfront about how it operates and has taken extensive measures to minimize the data it collects on users.

In research on six major browsers conducted by Douglas J. Leith, a professor from the University of Dublin’s Trinity College, the Brave browser was found to send the smallest amount of user data back to the developer’s servers.

The Brave browser is free, ad-supported software, and under our broad definition, it isn’t unreasonable to call it adware. However, because of Brave’s approach to privacy and user control, it’s hard to view its funding model as harmful to users.

Let’s be clear that Brave is unusual, has a relatively small user-base, and short history, so it’s hard to determine whether its business model is sustainable in the long term.

While it’s not perfect, it’s a good example of adware that meets most of our criteria listed above, at least from the perspective of users. Publishers and their advertisers probably have very different opinions about it.

Windows 11

If you’re a Windows 11 user, you may think that this is an unusual inclusion. But that’s because Microsoft has been so crafty that many users may not even realize they are being served with ads in one of the world’s most relied-upon operating systems.

When you investigate Windows 11 more thoroughly, it blurs the lines between paid software, ad-supported software and malicious adware to such an extent that it’s one of the primary reasons we have taken such an unusual approach to the topic of adware. Though, to be fair, it is marginally better than its predecessor, Windows 10.

First of all, Windows 11 is paid software. Its price is assumed to be included when we purchase a new computer that comes with it, otherwise the Home version sets you back $139 (at the time of writing).

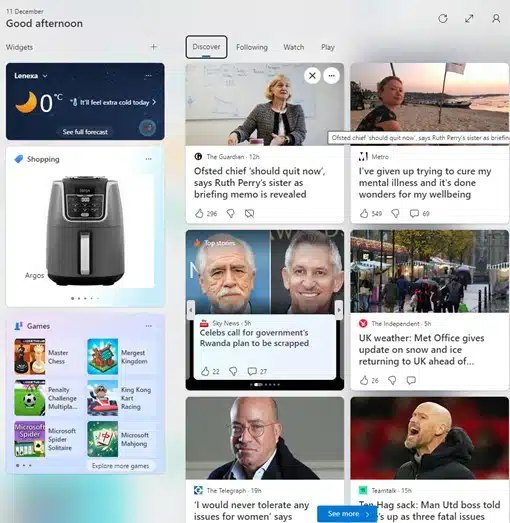

Don’t believe that your version of Windows has ads? Open up the widgets board by clicking in the bottom-left corner of your screen. You’ll immediately notice adverts for games and shopping sites.

Windows 11 also serves unwanted advertisements via “suggestions” or “tips”. Adverts are subtly – and not so subtly – used everywhere from the Action Center to the available apps listed in the Start menu.

If you use alternatives to Microsoft software, such as Chrome or Firefox, instead of the Edge browser, you’re likely to get regular suggestions from the Action Center to switch over to Edge. File Explorer often shows you ads for Microsoft’s OneDrive and Office365. Users may also be subjected to pop-up windows advertising third-party antivirus software.

You may not have even realize when notifications and suggestions are actually advertising Microsoft products, but they’ve surely inconvenienced you. They take up part of the display screen, distract you when you are busy and occupy valuable mental real estate – without offering much in return. After all, this Windows 11 is software that you’ve already paid for.

While there’s no rule that says paid software can’t also include ads to provide an additional source of revenue for the developer, it’s hard to fight the impression that Microsoft is getting greedy and trying to double dip on its customers.

These ads are insidious not just because Windows 11 is riddled with them, but they are disguised in such a way that many users probably never realize they are being advertised to. Alongside the ads is a bunch of bloatware, and together they take up screen real-estate, occupy space on your hard drive and can even slow down your computer.

Not only are the ads included by default, but it’s not that easy to get rid of them. You have to disable each of them individually, which most users probably can’t be bothered to do.

It gets even worse, because Windows also targets its ads specifically to you through its advertising ID. The Microsoft support page describes it as a “… unique advertising ID for each user on a device, which app developers and advertising networks can then use for their own purposes, including providing more relevant advertising in apps.”

While we may be used to this on Facebook, Google or anywhere else on the internet, this is happening right on our desktops, and it’s enabled by default.

Microsoft does offer a way for people to turn off its advertising ID, and presumably buries some kind of request for consent in its terms and conditions, but if most people have no idea that it’s even happening, they can hardly give any kind of informed consent.

On top of this, Microsoft also collects what it refers to as diagnostic data, which it claims is used “…to keep Windows secure and up to date, troubleshoot problems, and make product improvements…”

This data falls into two categories:

- Required diagnostic data – Includes information about your computer, its settings, capabilities and performance. This type of data collection can’t be opted out of.

- Optional diagnostic data – Includes more extensive information in each of the above categories, as well as details about the websites you visit, device usage, enhanced error reporting data, the memory state of your computer when an app or system crashes, and more.

You can check out what kind of data is being collected for diagnostics by going into Settings > Privacy > Diagnostics & Feedback and then downloading the Diagnostic Data Viewer tool. You can minimize the data that is collected on you by going to Settings > Privacy > Diagnostics & Feedback and switching the Send optional diagnostic data toggle to Off.

Windows 11 also collects data in many other ways, but going into each one would distract from the main point. The most important thing to internalize is that Windows displays ads and collects data in far more ways than people realize, using tactics that are eerily similar to malicious adware. These worrisome aspects are generally set up to run that way by default, and they are often related to features or programs that many users find a hindrance or may not want in the first place.

While the details may be included somewhere deep down in the user agreement, we all know that no one reads it. Another major issue is that most people simply don’t expect their operating system to collect this kind of information.

Most of us are aware that Facebook, Google and other tech companies do this, but they provide us with free services and have also attracted huge amounts of criticism in recent years. Meanwhile, Windows 11 has generally managed to slip past the mainstream media, meaning that much of this data collection is a surprise to users.

It’s shocking to think that such crucial software is playing a similar game to the companies whose business models revolve around advertising – especially because Windows 11 users have already paid for it.

When we go on to discuss adware in its traditional sense, you will see just how significant the overlap is between Windows 11 and the adware that we consider to be malicious.

In summary, Windows 11:

- Has ads in programs that the user may not have installed intentionally.

- Has ads that can arguably be called invasive and annoying.

- Has ads that can’t easily be disabled.

- Collects user data in a somewhat secretive manner..

- Is not upfront about these practices – it hides them as suggestions, and less savvy users may not even realize they are being marketed to.

- Includes most of these dubious practices by default – users have to first know about the dodgy practices, then opt out if they want to avoid them.

Facebook is another example of software that would never be considered adware in the traditional sense. One of the main reasons for this is that it was originally a website rather than something that was installed locally on your device or computer.

But Facebook has changed significantly since those days. It now gets the majority of its use through its app, and the platform has expanded its tentacles into realms of data collection and advertising that even the most serious adware connoisseurs can’t help but admire.

If we’re going to the effort of dragging Windows 11 into the topic because its behavior overlaps considerably with that of malicious adware, then it would be egregious to leave out the poster boy of data collection and targeted advertising.

Let’s round off some of the key points:

- Facebook is software.

- Facebook is supported by advertising.

- Users may consider Facebook’s ad placement intrusive or irritating.

- Facebook’s app manager is sometimes pre-installed locally on new devices.

- Facebook sometimes shows dangerous ads.

- Facebook collects exceptional amounts of data, including activity outside of the platform, and from people who aren’t even users.

- Facebook’s data collection practices are confusing, often active by default, and difficult to opt out of. Admittedly, they have improved significantly in the past few years, but there’s still a long way to go.

Many of these topics have already been beaten to death elsewhere in the media, otherwise, you can check out some of the links above. The point is that Facebook and its applications often act in ways that are comparable to more malicious types of adware.

Although Facebook does offer us services in exchange for these practices, we would be ignoring the elephant in the room if we told you to rid your devices of adware without telling you to be wary of something that can be just as invasive.

Facebook isn’t necessarily an exception. Amazon, Google and many more tech companies engage in similarly alarming practices. Even Apple’s iOS is sometimes seen as teetering toward adware. While it would be great to cover each in detail, it’s more important to delve into other types of adware so that we can demonstrate just how fuzzy the line is between the everyday and the malicious.

Potentially unwanted programs (PUPs) & malicious adware

Now that we’ve covered how some of our commonly used software overlaps in many ways with adware, let’s discuss some examples that fit in with the more traditional understanding of adware. First, we need to introduce you to PUPs, potentially unwanted programs that are far less exciting than the acronym may imply.

PUPs are basically unwanted software that you probably didn’t intend to download. They can be annoying, but they generally aren’t malicious or overly harmful. However, they often have the potential to introduce other threats to your system. They most commonly end up on your computer by being bundled with software that you do want.

For example, let’s say you downloaded a new program to unzip some files. When you ran the setup wizard, perhaps you weren’t paying a lot of attention and didn’t see that it also included a bunch of other programs.

When the setup finished, not only did you have your new unzipping program, but you may also have your browser hijacked to a new homepage and a new toolbar installed, both things that you never intended. At the very least, these might be annoying, but they could lead to further infections.

To be considered a PUP, the software itself shouldn’t be malicious and may even have legitimate uses. However, many examples straddle the border and are often hindrances to users.

A lot of adware falls into the PUP category, because as we’ve been arguing the whole article, the lines between different types of software are blurry, and their legitimacy is often subjective.

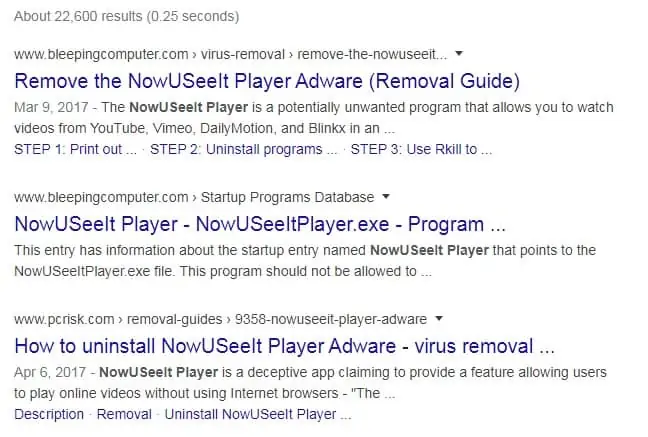

The NowUSeeIt Player

Now we’re moving into the territory of examples that are almost universally considered adware.

Most of the top websites describe the NowUSeeIt Player as adware.

The NowUSeeIt Player is often bundled with other software packages and sneakily installed on people’s computers, which has led it to be considered a PUP by many security-focused organizations.

One of the complications of the software – and another reason for why we have taken such a loose approach to the adware definition – is that the NowUSeeIt Player actually serves a purpose.

It’s a video player that allows its users to watch videos from YouTube, Vimeo, DailyMotion and other websites outside of their browser. To fund itself, it displays ads on its users’ computers.

The ads it displays can be quite intrusive, with popups displaying over whatever else you were doing. Some of its ads are also malicious, so it can easily lead users into downloading more pervasive malware.

The software also collects data about its users’ browsing activity, as well as various hardware and software information. This could include personal details, which are then shared with third parties.

This is obviously all bad news, and anyone that accidentally downloaded the NowUSeeIt Player should remove it immediately (you can follow either of the above links for instructions).

The interesting thing about it is just how many similarities it has with the previously mentioned examples of ad-supported software:

- It’s software with intrusive ads like Windows 11.

- It collects a lot of data like Facebook.

- It has a seemingly legitimate purpose.

The NowUSeeIt Player takes the negatives to the extreme, and is far more harmful than the other kinds of ad-supported software that we have mentioned. However, it’s hard to deny the overlap.

Maybe it is right to hold a traditional view and consider Facebook and Windows 11 ad-supported software, and the NowUSeeIt Player as adware or a PUP. The problem is, why? Is it just because the NowUSeeIt Player takes things a little too far? But where exactly is the line?

Few people in tech would ever recommend keeping the NowUSeeIt player on your computer because of all the negatives associated with it. While many of us still have Facebook and Windows 11, they’ve also had strong and reasonable campaigns against their use, even by mainstream publications

Appearch.info

Toward the end of our spectrum are programs like Appearch.info, which don’t even bother with the pretense of offering anything to infected users. Just like the NowUSeeIt Player, Appearch.info is generally bundled with other software so it can sneak on to peoples’ computers.

Once Appearch.info installs itself, its victims will notice its pop-up ads regularly intruding whenever they browse. The ads will display a message asking for further access. If users click to allow access, then they will also begin to see ads on their desktop, even when their browser is closed.

Appearch.info even changes the group policy settings for the Google Chrome browser, which stops victims from easily deleting the popup ads. On top of this, Appearch.info may also change the text on websites to hyperlinks, recommend fake updates, convince users to download fraudulent software or even install other harmful software without the users’ knowledge.

Appearch.info offers no benefit to those who accidentally install it. Not only are the ads distracting, but it can also introduce other threats to their computers. It’s only purpose is to make money for its developers.

Considering all of these factors, Appearch.info definitely falls into the category of a potentially unwanted program and is a great example of what we traditionally consider to be adware.

But when you really think about it, apart from its lack of benefits to users, it has a lot of overlap with some of our commonly used ad-supported software. If your system is infected with Appearch.info, you can remove it by following the instructions in the link above.

How to avoid adware

Confused?

That’s because the way we normally think of adware doesn’t make a lot of sense. As we mentioned at the start, it’s much more reasonable to think of adware as a spectrum that ranges from completely legitimate ad-supported software, through to the questionable ad-supported services that most of us use every day, all the way to examples like Appearch.info that harm users without offering any benefit.

The distinction may have made sense in the past, but invasive advertising practices and widespread data collection have become so mainstream, that there is no longer any point where you can clearly draw the line.

When it comes to avoiding adware, each of us will have different tolerance for what practices we accept. It’s pretty clear that no one would want Appearch.info on their system, but what about the NowUSeeIt Player or even Windows 11?

Not too many people are ready to switch over to a less-invasive alternative like Linux, so perhaps the best option is to learn about the potential harms of each, when it is best to avoid a certain service, and how we can minimize any negatives.

Ad-supported software

Some adware is relatively legitimate, and there may not be many significant reasons to avoid it. The Brave browser that we mentioned at the start is a great example of how advertising can be used to support software development without pushing too many obnoxious ads or invading user privacy.

While we don’t necessarily need to avoid all ad-supported software, it is important to find out what the ad-supported software we use does, and whether it engages in any practices that we consider harmful, unnecessary or extreme.

The response is up to the individual, because the practices we object to are subjective. One of the major problems is that many of us use so many different kinds of ad-supported software that examining each option in depth is impractical for all but the most dedicated tech-heads.

If we’re being realistic, it isn’t possible for the average user to avoid all adware. It simply takes too much time and knowledge, and you would also have to stop using a bunch of software that many consider essential to their work and social lives.

As a start, you would either have to stop using or make significant configuration changes to the following:

- Windows 11

- Google Search

- YouTube

- Amazon

- Netflix

- Spotify

This list is just a tiny fraction of the common software that engages in at least some questionable practices. Covering every program or service that has intrusive ads or collects an unreasonable amount of data just isn’t feasible.

If you are concerned about these issues, the best approach is to look up services that specifically avoid these practices. A site like privacytools.io is a good place to start, and includes a wide range of software available under paid, ad-supported, freemium and donation-based funding models.

On top of avoiding or changing the settings in all of the software you use, you can also take steps like running an adblocker like uBlockOrigin and a script blocker like NoScript.

If you are looking to completely protect your privacy and prevent data collection, the honest answer is that it isn’t really feasible without making extreme changes to the way you engage with tech.

You would have to always use TOR, a trustworthy VPN, a range of other tools, multiple aliases and have outstanding digital OpSec capabilities to have true privacy. While this is beyond most of us, being mindful of when and what types of data are being collected, as well as when to use privacy tools can take you a long way.

You can start simply by doing things like blocking cookies in you browser, and removing unnecessary app iOS and Android permissions on your devices.

Potentially unwanted programs (PUPs) & malicious adware

Avoiding PUPs and outwardly malicious adware is much simpler. All you have to do is follow general cybersecurity best practices and you should be able to keep much of it at bay. One of the most important things you can do is be wary when installing software, particularly if you are looking for free options.

For example, let’s say you’re looking to download a free PDF editor. When you run a search, some of the first websites to come up in the results will be the likes of Softonic, CNET and Softpedia, which act as software libraries.

These sites have cleaned themselves up significantly in recent years, but they have a long history of bundling adware alongside the software they house.

While these sites have improved their practices, they aren’t necessary in most cases. You can often skip the middleman and download software direct from the developer. But you need to make sure the developer isn’t engaging in any dodgy practices either.

How do you do this?

To start with, you can inspect the software to see if it is packaged with PUPs or things that you don’t need. A small portion of people will also be able to take a look at the source code of the software that they use.

For everyone else, the only way you can find decent software is through putting your trust in the right places. This could involve:

- Trust in an organization – Some organizations like the Mozilla Foundation or the Electronic Frontier Foundation (EFF) have good reputations, so you can generally feel secure in following most of their recommendations.

- Trust in a tech review site like Comparitech – We go out of our way to make sure we recommend great software to our readers.

- Trust in a community – Whether it’s an online community like the Open Source subreddit, or simply people in your life who are dedicated to tech, these can be good places to turn to for finding decent software.

Adware doesn’t just come from bundled software. You can also encounter it in your general online activity. To protect yourself, you should:

- Only visit trusted websites.

- Never click on or download anything that you aren’t sure of. If in doubt, avoid it, or at least ask someone more knowledgeable.

- Run antivirus and antimalware solutions such as Windows Defender and Malwarebytes.

- Always update your software as soon as possible.

When it comes to mobile devices, it’s best to only use the official app repositories, such as Apple’s App Store or the Play Store. More advanced Android users can also try out F-Droid for free and open source (FOSS) software.

Adware has been known to sneak into the App Store, and the Play Store, so sticking with them isn’t enough to keep you safe. You should also make sure that you are only using trusted apps from known developers, which you can find using the tips listed above for safe software.

How to remove adware

If you have noticed ads popping up everywhere in your phone or desktop, or your browser being redirected to strange websites, then there’s a good chance that you’ve accidentally downloaded adware somewhere along the way.

In simple cases, you may be able to remove it quite easily. If you can find the adware program, follow these instructions for your operating system to remove it.

Here’s how to remove adware (from Android, Chrome or iOS):

- Windows – Press the Windows key, click the All apps button and look for the program, right click on it and hit Uninstall. Alternatively, you can go into the Control Panel, go to Programs, then Programs and features, look for the offending software, right click on it, then click Uninstall.

- Mac – Open Finder, then click on Applications. Search for the adware, then right click on it. Click Move to Trash, then go to the Trash Can in the Dock, right click on it, then select Empty Trash.

- iOS – Go to Settings, then General, then Storage. Select the offending app, then touch where it says Delete app. Tap Delete to confirm that you want to remove it.

- Android – If you can find the adware app on your Android device, simply hold it down and begin to move the app with your finger. You will see Uninstall pop up in the top right. All you have to do is drag the app over.

In many cases, the adware will be more advanced, and not so easy to remove. If the above doesn’t work, your next best bet is probably to install Malwarebytes, which you can download for most platforms by clicking on the link.

Once you have installed it, run a scan, and see if it picks up the adware. If it does, simply follow the cues from Malwarebytes to remove it. Once it has finished, your computer should be good to go.

If neither of these options work, then you may have something more serious on your hands. If this is the case, one of the easiest options is to reformat your computer and restore it to an earlier point. Make sure to create backups of what you need first.

If this isn’t an option, you can try some of the more advanced solutions available. In many cases, the adware shouldn’t be too difficult to remove. Despite this, it’s best to take precautions and avoid adware wherever possible. Not only is it annoying, but it can also lead to more serious computer issues.

This is why it’s so important to follow good security practices whenever you’re online. Not only will you save yourself from insufferable ads, but you’ll also prevent yourself from having to waste a few hours fixing your system.