Apple recently filed multiple patent applications concerning the ways identification data can be requested from an iPhone and how the iPhone owner can be authenticated. This is in preparation for digital identification, including digital passports. Your iPhone can already replace your physical wallet by holding digital versions of your bank and credit cards. Now, Apple is pushing for your iPhone to replace your physical, paper ID – even your passport.

Writing a piece about digital passports is writing about digital ID. Whether it’s digital driver’s licenses or digital passports, we’re talking about digital ID. And in this humble writer’s opinion, the benefits of digital ID are overwhelmingly dwarfed by the potential pitfalls. Expose yourself to identity theft and electronic profiling (and more…) for the convenience of not having to carry an extra document? It seems kind of silly.

This post looks at Apple’s proposition, based on its patent applications, and weighs the benefits against the pitfalls. Do we need – or even want – digital identification?

Full disclosure: you already know where I stand.

Let’s start.

Apple’s digital passport

This recent patent filing isn’t the first time Apple has pushed iPhones to replace traditional identification. In 2018, Apple enabled iPhones to act as a digital ID for student campuses in the US. And even as far back as 2015, Apple Vice President Eddy Cue stated that using iPhones as digital passports was in the company’s future plans. Also, the iPhone, via its Wallet app, can already host the digital versions of your bank and credit cards, as mentioned above.

Digital identification is in Apple’s cards.

The patent application itself isn’t solely focused on digital passports. It is more generally focused on digital identification and goes over many different use cases. Having taken a strong stance on user privacy in recent years, Apple goes into how digital identification can work securely and privately – and that’s laudable. Still, it may be little more than wishful thinking. I’ll lay out my arguments further down and leave it up to you to make up your mind about that.

Now, there are two scenarios in Apple’s application that exemplify the crux of the proposed functionality. Let’s quickly look at each of them.

Confirming attributes

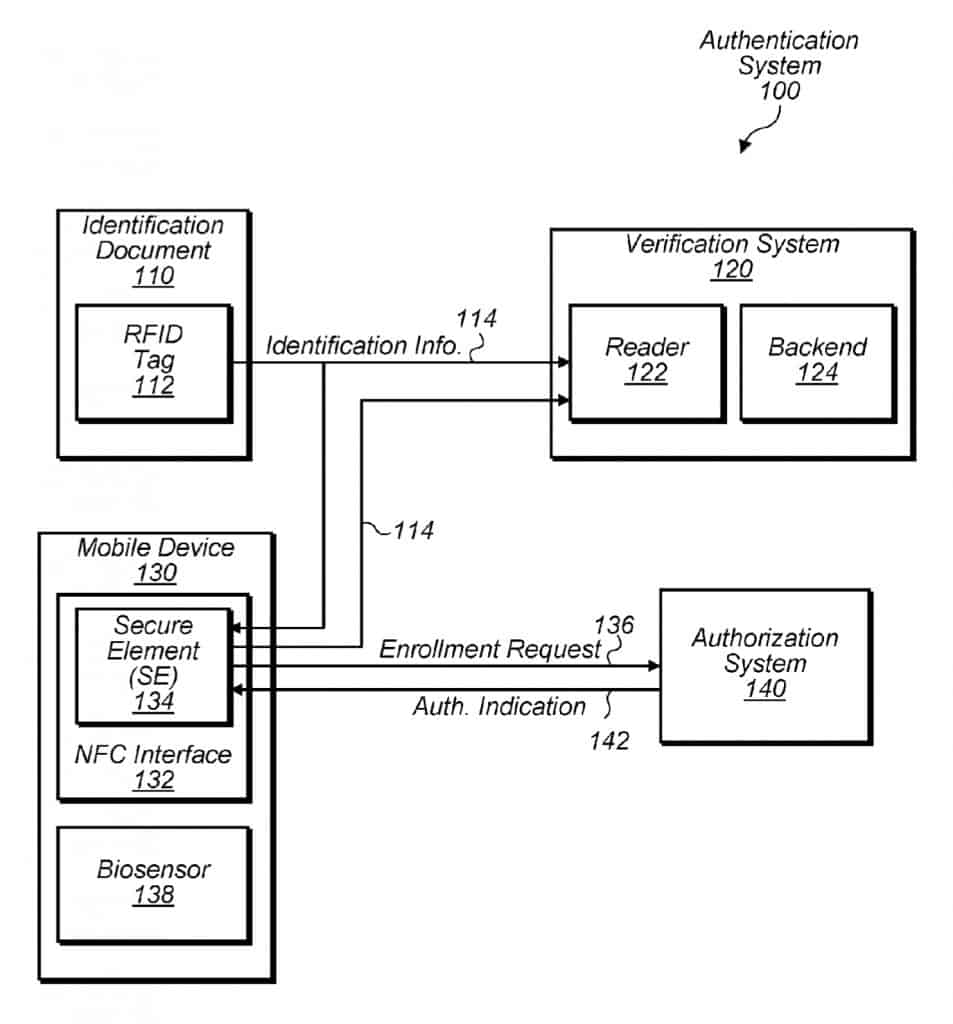

The first scenario from Apple’s patent application exemplifies how an iPhone could be used to replace traditional identification to confirm one of the iPhone holder’s attributes.

“In some embodiments, the mobile device may perform an authentication that includes the secure element confirming whether a holder of an identification document has an attribute satisfying some criterion without providing that attribute (or at least providing some information about that attribute without providing all information about that attribute). For example, in one embodiment, a person may be attempting to purchase an item that requires the merchant to confirm whether an age of the person satisfies some threshold value. In such an embodiment, rather than having the user present the identification document (e.g., a driver license), the reader of the merchant may ask the secure element to confirm whether the user of the mobile device is old enough to purchase the item. Based on a stored date of birth and a successful authentication of the user (e.g., via a biosensor), the secure element may then answer in the affirmative or the negative (as opposed to actually communicating the user’s age or date of birth). In doing so, the mobile device is able to protect a user’s identification information, yet still adequately answer the merchant’s inquiry.”

Apple devices have a feature called the secure enclave. The secure enclave is a subsystem found on all iOS devices. It is isolated from the main processor in order to secure the sensitive user data it holds. This isolation ensures the data held in the secure enclave cannot be accessed even when the Application Processor kernel becomes compromised.

The secure enclave is where your biometric data for facial recognition, for example, is stored on your iPhone. Your payment information for your cards in the Wallet app also resides in the secure enclave.

The identification system, detailed in Apple’s patent application, revolves around how the iPhone would provide information from the secure enclave and, crucially, how much of it to expose. Limiting the exposed information to what is strictly necessary for the transaction is key.

The example used is when a person must confirm their age to purchase a product. Instead of providing traditional identification, such as a driver’s license, the iPhone user could present their phone to the merchant’s reader. The reader then queries the secure enclave to confirm if the iPhone user is of legal age to purchase the product in question. A Yes or a No relative to whether the person is above the age threshold required to purchase the product would be returned – not the actual person’s age.

This can be seen as more privacy-preserving than presenting a traditional ID-which would reveal the person’s actual age and potentially other sensitive data (home address, numeric identifiers, etc.)

Authenticating the requesting party

The second scenario that interests us from the patent application exemplifies how an iPhone holder could authenticate the requesting party.

“Authorization system 420, in one embodiment, is a computer system to facilitate enrolling a merchant system 410. In some embodiments, authorization system 420 may be operated by an authority that issues identification document 110 or a trusted third-party that interacts with the issuing authority. In some embodiments, merchant system 410 may begin an enrollment by having backend 414 generate a public-key pair and issuing an enrollment request 422 that includes a CSR for the key pair. In some embodiments, enrollment request 422 may also specify what attribute or attributes that merchant wants SE 134 to confirm. For example, in one embodiment, the request 422 may specify that a merchant wants to 1) know whether a user exceeds a particular age threshold (e.g., is over 21 years of age) and 2) be provided with a corresponding photograph of the user that is present on identification document 110. Authorization system 420 may then validate this request 422, which, in some embodiments, may be performed in a similar manner as discussed above with respect to request 136. In response to a successful validation the request, in various embodiments, authorization 420 issues a corresponding digital certificate 424 indicating that merchant system 410 is authorized to receive the request information specified in its enrollment request 422. In some embodiments, upon merchant system 410 receiving certificate 424, backend 414 may distribute the certificate to readers 412 in order to enable them to issue requests 426. In another embodiment, rather than providing a merchant system 410 with a certificate, authorization system 420 is configured to make backend 414 an intermediate certificate authority, which has the ability to issue certificates to readers 412 for public key pairs generated by the readers 412.”

Pretty simple, right? Let’s break that down.

The above example demonstrates the use of this functionality with passports. And what it states is that when passing through customs, the customs agent will need more information on you than if you’re over 21 years of age. In the above example, the request is for an age threshold confirmation and a picture of the iPhone holder.

But before your phone starts spewing out multiple sensitive data points, the requesting party will need to prove they are authorized to request these data points. And Apple’s proposed system to achieve this works in the same way as to how HTTPS works over the internet.

Every HTTPS-enabled website is issued a server certificate from an official certificate authority that can be validated against the certificate authority’s certificate. These certificate authority certificates are included in all modern browsers. So when you visit an HTTPS-enabled website, the site presents its certificate to your browser, which validates it against the CA’s certificate. If they match, the site loads. If they don’t, you’ll see a warning page in your browser stating that there was a certificate mismatch and that continuing on to the site in question is not recommended as its identity can’t be verified.

And that’s exactly what Apple is proposing to authenticate the requesting parties. Just as your web browser validates the identity of the websites you access, your phone would validate the requesting party’s identity. Like your browser, your iPhone would contain the CA certificates. And it could authenticate the customs agent (in this example) by accepting or rejecting their certificate.

Wishful thinking?

That all sounds good to me: don’t provide more information than what’s needed and authenticate the requesting party. It all makes sense. Unsurprisingly, Apple is trying to get this right and make sure privacy and security are baked into its functionality. And I have no advice to give to Apple engineers and programmers, who are all very smart and qualified people.

But the fact is that our personal information is not very well protected from a legal perspective. That’s why we read news stories about mismanaged user data by corporations every few days – and data breaches every few weeks. A private company’s patent application detailing how secure and private its proposed technology could be doesn’t do much to solve that problem.

No technology is ever going to be 100% invulnerable. HTTPS, for example, while definitely being a huge step up in security from plain HTTP, is still far from perfect. Certificates expire, they can sometimes be spoofed, CAs can change, and the HTTPS system may be vulnerable to Man-in-the-Middle attacks in some situations. What would the effects of that be on your ability to identify yourself?

Then there’s the fact that every time someone uses their digital ID, it creates an opportunity for the ID issuer and the ID verifier to collect information on that person. Suppose we use the first example in Apple’s patent of someone needing to prove they’re old enough to purchase a particular product. In that case, the ID verifier, not the merchant, could note and record the ID holder’s age status and location. The merchant could record that data from a traditional ID. But in this scheme, the verifier is an additional party that has the opportunity to electronically record their personal information.

Even if the transmission of that credential doesn’t contain any other personal information, their payment information may be associated with the transaction and collected. This would quickly end up constituting a user database. And that database could be sold to data brokers, stolen by black hat hackers, abused by rogue employees, or seized by police or immigration officials.

As for the authentication of the requesting party – of course, this is required. But even if authenticated, the requesting party can still abuse their position. Take the example of an ID holder presenting their digital ID to a police officer. The officer would be authenticated as being a real cop from the local police department. The officer may have a legitimate reason to request some personal information from you, but not necessarily all of your information. Nothing would stop them from pulling as much information as they can from the database(s) your digital ID is tied to, regardless of whether the situation warrants it or not. And they may be getting more information from your digital ID than from your regular, old-school, printed ID, which is limited to what is displayed.

The above creates new risks for certain communities, such as immigrants and people of color, who are already disproportionately vulnerable to discrimination and abuse by police.

Then there’s the issue of privilege. In devising these systems that aim to make personal information more portable and easy to share, we should consider:

- The current laws around data protection

- The lack of access to technology in many segments of society

We need to be mindful of the technology systems we build. Their aim should be to reduce discrimination and exclusion rather than escalating them. We’ve already got enough classes in our society – let’s not create more.

Unanswered questions

We also need to consider that the use of such technology raises many difficult questions to answer.

For instance, the proposed system is from Apple, an American corporation. In today’s geopolitical landscape, not every country is aligned with the United States. Is it likely that countries that oppose the US would adopt a system created by a US corporation – especially on such a sensitive issue? Probably not.

Then there’s the question of stamping a digital passport – how is that done? Some countries will bar you from entry if you’ve previously visited countries on their blacklist. The UAE, for example, may not let you into the country if you have an Israel stamp. Can different immigration authorities see travelers’ itineraries to other countries?

There are also certain security issues that come into play.

Such a system would inextricably tie your identity to your phone. What happens if you don’t have your phone with you? What happens if it’s lost or stolen? And linked to that point is the fact that most of us don’t carry our passports with us at all times, unlike our phones. Sensitive documents are better secured at home when not being used.

And if your means of identification is tied to your phone, that means you may well be handing your phone over to third parties, who may be in a position to go beyond simply identifying you and could do unauthorized things with your phone. An opportunity that does not exist with a traditional paper passport.

Another concern is that biometric identification isn’t as seamless as some of its supporting marketing makes it out to be. In practice, biometric identification is far from perfect, and is susceptible to fraud, misidentification and abuse, as we’re about to see with the example below.

Mission creep

I’m aware that the “slippery slope” argument isn’t necessarily a valid one. Green-lighting digital identification for certain things doesn’t mean we’re on our way to implementing a National digital ID. But the risk is real. And some countries, such as India, did roll out a National digital ID scheme called Aadhaar. This Hindi word loosely translates to “foundation.” And the story behind India’s Aadhaar digital identification system can shed some light on the potential consequences that come from the use of such technologies.

India’s Aadhaar, introduced in 2016, consists of a unique string of 12 digits, provided to each resident of India, which is linked to that person’s biometric and demographic data, held by the government. Aadhaar is considered the largest biometric-linked national ID system globally, with more than 1.14 billion unique identity records.

Its stated goals were to improve efficiency in welfare distribution and foster greater social inclusion. However, the scheme’s privacy and surveillance risks made it controversial from the outset. And its rollout and management suffered some pretty catastrophic fumbles. Some of the issues were:

- The issuance of duplicate and fraudulent identity records

- The widespread misuse of Aadhaar data by government agencies and private contractors

- The denial of basic social services to those whose identities cannot be verified through the system.

In 2018, Aadhaar was challenged in India’s Supreme Court, which declared many – though not all – of Aadhaar’s dispositions as being unconstitutional. Despite it being somewhat less repressive than it originally was, Aadhaar has still failed in its stated mission of social inclusion and better welfare distribution.

On the “slippery slope” front, Aadhaar initially worked just like Apple describes its digital ID scheme in its patent application. It returned a Yes or a No if a person’s biometric and demographic data matched the data captured when the individual enrolled in the program. However, later in 2016, the authentication mechanism was changed. In the new authentication scheme, querying the Aadhaar database to confirm a person’s status would return that person’s information rather than simply a Yes or a No.

As we get used to the use of a particular technology, we tend to use it for broader and broader purposes – that, in itself, is mission creep. And looking at how things panned out with India’s Aadhaar, it pretty much jumps in your face that Indians were better off without Aadhaar, no? Inserting technology into everything is not necessarily the best way to go. And just because we can do something doesn’t mean we should.

Take electronic voting machines. We can do it. And electronic voting machines do exist and have been used before. But the difficulties in creating a secure, tamper-resistant electronic voting system prevent us from implementing it on a large scale – and rightfully so. We have a voting system that may not be perfect, but it works. And we have manual recounts in case of anomalies or other issues. We don’t need a new system, let alone one that comprises so many black boxes as to render them opaque to the vast majority of its users. We have an increasing tendency to solve problems that don’t really exist with technology. And we’re worse off for it, most of the time.

Conclusion

On the surface, it may seem that we’re simply moving towards greater convenience and practicality. But the reality is that we may well be creating solutions that are much worse than the problem. I mean, do we have trouble properly verifying people’s age before they can buy a six-pack? Are our borders overrun by evil passport counterfeiters that the current system simply cannot control? Are we crumbling under the weight of all the ID cards in our wallets?

The answer to all of those questions is no. So why reinvent the wheel? It may be that reinventing the wheel is highly lucrative for the corporation doing the reinventing. As would be passing it off as one of the hundreds of so-called “revolutions” we’re now accustomed to witnessing every few months…

And again, the tradeoff could potentially be huge. Such systems could undermine our democracies. We should not take this issue lightly. It’s about a lot more than how many cards are in your wallet.

The bottom line is that building digital identification systems is much easier than dismantling them. So we should think long and hard before going down that path.

What can I do to protect my privacy and security?

If you’re concerned about your privacy you may find some of the following tools helpful.