Want to know about all of the ways your mobile phone tracks you? Take some deep breaths and settle in, because it’s far from a short list. Unless you live deep under the sea among the lantern fish, you are probably well aware that large amounts of personal data are constantly being harvested. However, you may not be as aware of the many complicated ways that data is collected, nor what happens to it all afterward.

Where it ends up really depends on the situation. Some of it is kept briefly then disposed of, some is kept long term. A lot of the time it’s used to train algorithms. Large amounts are traded or sold. Sometimes it’s used in targeted ads for businesses. At others, it’s put to work by political parties to get the edge in the next election. Sometimes the data is even handed over to various government agencies.

You may think that much of this data collection can’t be particularly harmful. After all, who cares what football team you like or what websites you look at when you’re bored? But, when such seemingly insignificant data points are combined with all of the other data collected by tech giants through their various services, it starts to build up into detailed profiles.

When combined with data that’s traded, shared or bought from other companies, the results can be truly terrifying. These systems can know what you eat, who you vote for, what you like to watch, who you have relationships with and much more. There are concerning implications of this type of all-encompassing surveillance, and they reek of Orwellianism.

Mobile phone tracking is an intricate web that involves many complex mechanisms and an even greater number of entities. While it’s hard to bring order to such a tangled mess of data collection, we have roughly arranged our investigation by who is collecting the data:

- Your network provider.

- Your phone manufacturer and operating system.

- Your applications and third parties.

- Hackers.

- The government.

Although we have tried to be as exhaustive as possible in this guide, the surveillance system is so complex that there is no way we could thoroughly document it all in an article without it being hundreds of pages long. With this in mind, it’s reasonable for you to assume that there are a bunch more nefarious tactics that we couldn’t cover, as well as even more that are yet to be widely known.

Network providers

Network providers like AT&T, Verizon and their international equivalents provide the infrastructure that allows you to call, text and use the internet. This gives them extensive insight into what goes through your phone.

Obviously, they have logs of your calls and messages, which include:

- Who the other party is.

- The time it took place, and its duration (for calls).

- Which towers you were near (discussed in more detail in the Can your phone track you when the location is turned off section).

- The content (for text messages).

Your service provider won’t normally record the contents of your calls, but can do so if it has received requests from law enforcement.

Let’s have a look at a company’s privacy policy to see what else they collect. We’ve chosen AT&T at random, but for the most part these companies collect similar information. Some of the highlights include:

Web browsing and app information – This “includes things like the websites you visit or mobile apps you use, on or off our networks. It includes internet protocol addresses and URLs, pixels, cookies and similar technologies, and identifiers such as advertising IDs and device IDs. It can also include information about the time you spend on websites or apps, the links or advertisements you see, search terms you enter, items identified in your online shopping carts and other similar information.”

As you can see, they get records of pretty much all of the internet activity that goes on through both your browser and apps. Worryingly, AT&T includes the phrase “…on and off our networks.”

As you can see, they get records of pretty much all of the internet activity that goes on through both your browser and apps. Worryingly, AT&T includes the phrase “…on and off our networks.”

Equipment information – It’s hard to tell from the wording of the privacy policy, but this includes information related to “…the type, identifier, status, settings, configuration, software or use”.

Presumably, it includes things like your device’s identification number, operating system, language, and much more.

Network performance and usage information – Again, this is a little confusing, but it covers “… information about our networks, including your use of Products or Services or equipment on the networks, and how they are performing.”

This seems to include data from how you use your phone over the company’s network.

Location information – It is “… generated when the devices, Products or Services you use interact with cell towers, Wi-Fi routers, Bluetooth services, access points, other devices, beacons and/or with other technologies, including GPS satellites.” It can include where your device is located, your street address, and ZIP code.

To top off this information smorgasbord, your network provider also has your account and billing information, including your contact details. Unfortunately, it gets worse. Not only does your network provider know who you are, who you communicate with, and the sites you access from its own data collection practices, but it also complements this data with information from outside sources. Some of those listed by AT&T include:

- Public posts to social networking sites.

- “Commercially available geographic and demographic information”. For those out of the loop, “commercially available” is usually code for information you can buy from other companies — known as data brokers.

- Credit reports.

- Marketing mailing lists.

But having all of this data isn’t enough. Network providers also share the data with other entities. Again, these privacy policies can be complex and written in elusive ways—if not intending to straight-up mislead people, then at least to confuse them.

While they may try their hardest not to say it outright, network providers do—at least in part—sell your data. They also share data with the government upon request. In 2013, for example, Verizon was compelled to secretly share the daily call records of millions of its customers with the NSA.

Device manufacturer, operating system & default apps

If you have an iPhone or a Google Pixel, the device and its operating system are built by the same company. Most other common smartphones usually feature Google’s Android OS on a Samsung, Huawei, Lenovo, Oppo, or other brand’s device.

This generally means that these devices have software from Google and the manufacturer, both of which are capable of collecting your data. The manufacturer software is often seen as unnecessary bloatware and can be removed.

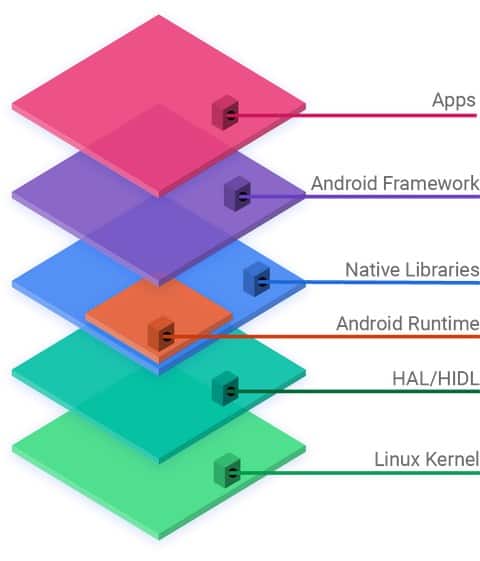

It’s important to understand that while Android is developed by Google, it’s actually open source at its core. The Android Open Source Project (AOSP) publishes the code openly, and it is adapted to form a range of other software. This ranges from the OS for the Kindle Fire eReaders, which send their data to Amazon, to LineageOS, which is a minimally invasive version of Android.

The layers of the Android ecosystem. The Android Open Source Project licensed under CC0.

Android devices with Google Mobile Services

The most common form of Android on smartphones comes preinstalled with Google Mobile Services (GMS) and Google Play Services. Essentially all of the Android smartphones that you regularly see—from Samsung Galaxies to budget Motorolas—have licenses from Google to preinstall this software.

At a minimum, GMS includes apps such as Google Chrome, YouTube, Google Search and Google Play. However, other popular apps like Gmail, Google Drive and Google Maps can also be part of the package.

In most of these smartphones, this combination of Android and GMS is topped off with the device manufacturer’s software (unless it’s a Google Pixel). The manufacturer will end up with a bunch of data, but it overlaps a lot with what Google collects.

While manufacturers like Samsung offer a range of their own data collecting apps, such as Samsung Pay or Bixby, these pale in comparison to Google’s entire data collection ecosystem.

Because you probably use far more of Google’s services than those of your device manufacturer, it’s reasonable to assume that Google ends up with much more of your data. While we will focus on Google’s collection, keep in mind that your manufacturer has access as well. This has been of particular concern in China, where researchers have shown that phone makers like Xiamoi and OnePlus collect large amounts of sensitive user data — and disproportionately from Chinese citizens.

One of the key differences between Google and the respective phone-maker is that your device manufacturer may sell your data, while Google technically doesn’t, although it’s debatable whether this distinction really matters.

Companies like Samsung and Google don’t like to break down their privacy policies by individual products or services, so it’s hard to tell exactly what each app or service sends back to the company servers on its own.

For the sake of simplicity and because these providers are so coy in their privacy policies, we won’t get too specific.

Google’s data collection

If you’re an Android user with Google Mobile Services on your device, one of the best ways to get an idea of what Google is collecting on you is to just ask it. You can download the data Google has collected on you through the dashboard of your Google account. This Dashboard also lets you see all of your linked services in one area.

Unless you are privacy paranoid, the file Google sends you will include a ton of data, covering things like:

- Location history, including all of the places you have been

- In-app activities

- Web searches

- Watched videos

- Apps and extensions

- Bookmarks

- Contacts

- Emails

If you use Google services elsewhere, this data won’t give you a perfect representation of what Google collects purely through your phone. If you use Google Search, Chrome, Maps, or YouTube on your computer, this data will also be included. Despite this, it should still be eye-opening for you to see what the company has been able to collect about you.

Because Google Play Services and the Play Store are integral for downloading and running third-party apps, Google can also access data about other apps. An investigation by The Information discovered that Google had an internal program known as Android Lockbox, which company employees used to look up how users engaged with third-party apps.

Android Lockbox accessed the data about other apps through Google Mobile Services. While the data was anonymous and wasn’t personally identifiable, The Verge reported that its sources claim Google has used the data to “keep tabs on rivals to Google’s Gmail service or to monitor Facebook and Instagram usage.”

A study from Vanderbilt University gives us a different type of insight into Google’s data collection practices. It found that during a 24 hour period, a stationary Android phone with only Chrome active in the background communicated location data to Google 340 times. This is for a phone that isn’t even being used.

In another phase of the experiment, the researchers looked at Android’s data collection when most other Google products were deliberately avoided, except for Google Chrome. During a day of what the study termed “typical use”, it found that an Android device collected the user’s location approximately 450 times. It made 90 requests per hour, the biggest slice of which were to advertising domains.

In total, 11.6MB of data was collected by Google each day, about two-thirds of which was split between location data and calls to Google’s advertising domains. Remember, this is for people who weren’t using Gmail, Maps, YouTube and the many other popular services. It’s safe to assume that the amount of data would have been significantly greater if these were also being used.

However, it’s important to note that the pure volume of data being sent to Google’s servers isn’t necessarily a reliable indicator of the amount of personal data, or the sensitivity of such data. We could be charitable to Google, but since the company insists on making its privacy policy and configuration settings too complicated for the average user, we won’t judge you if you assume the worst.

The study also found that Android devices were sending through MAC addresses, IMEI numbers and serial numbers alongside users’ Gmail IDs. It also claimed that Google had the potential to deanonymize data through its various streams of data collection.

Google’s data collection on iPhones

If you have an iPhone, but still use services like Chrome, YouTube, Google Maps or Gmail on it, Google will still get data through these apps. You may want to check out what data Google manages to collect through your iPhone using the steps listed in the previous section.

The same Vanderbilt University study found that an idle iPhone would send 0.76MB per day to Google servers, averaging just under one request per hour. These requests were usually advertising-related. When the iPhone was used in a typical manner, it was found to send 1.4MB to Apple each day, with about 18 requests per hour.

While this stage of the study involved deliberately avoiding most Google products (except Chrome), it does show a significant difference between the two company’s practices. There were no ad-related calls to Apple’s servers, and it sent less than 1/16 of the amount of location data that Android phones sent to Google servers.

However, the use of Chrome and Google’s extensive ad infrastructure across the web meant that iPhones were still sending about 50 requests per hour to Google servers, totaling almost 6MB. Almost all of this data involved calls to ad domains.

Google has even paid Apple billions to be the default search engine on Safari. While Apple tends to have a much better privacy reputation, it’s hard to deny that it has also been complicit in the data collection of its users.

Apple & iOS

If you want to take a look at the data Apple collects on you, you can download it by logging in at privacy.apple.com. Follow the prompts under the Obtain a copy of your data section to get sent a copy.

While this may include data Apple has acquired outside of your device, it will give you decent insight into what types of information the company collects. The data can include things like your:

- Apple ID account information and login records.

- Call history.

- Data stored on iCloud.

- Browsing history and purchase records from iTunes, Apple Books and the App Store.

- Purchase records from Apple retail stores.

- Information from Apple apps such as Game Center, Apple Music, iCloud and the Health app.

Compared to Google’s data collection, Apple’s practices seem relatively benign. The company can afford to be, because a significant portion of its income comes from paid hardware, as opposed to Google’s business model of mostly ad-supported free software.

Apple hasn’t been immune to bugs or privacy scandals, but it does seem to be making privacy more of a focus in its products. A good example is the release of iOS 14, which included privacy-enhancing features such as:

- An indicator of when apps are accessing the camera or microphone.

- Granular configuration options for location and photo permissions.

- Randomized MAC addresses.

- Notifications if apps are accessing clipboard information.

- A feature that will require apps to ask for permission to track you across websites and other apps, due next year.

The release of iOS 15 in 2021 added yet more features. These included:

- Preventing senders from using invisible pixels to collect information — such as an IP address — about the user.

- Providing a rundown on which of the device’s sensors each app has used in the last seven days and the domains accessed during this period.

- Information on which third-party domains an app is contacting — and potentially sharing user data.

- Hiding users’ IP addresses from trackers.

But, while Apple devices may collect less data, there is still a lot that the company can improve on.

Apps

We have partially talked about the data collection of apps from Google, Apple and device manufacturers, because the lines between the types of data collection are so murky. However, there is still much more app-related data collection to cover.

Officially, apps are downloaded from the App Store or Google Play. These are generally vetted by their respective owners, with Apple having a better record for keeping the worst apps out. However many common apps will still suck up tremendous amounts of data. Remember the old adage that has become a cliché in our age of free software: If you aren’t paying for the product, then you are the product.

Apps can access whatever data to which they’ve been granted permission. These days, you will notice permissions when you try out new functions on your apps. They will ask for permission to access things like your microphone, camera, location, storage and much more. Most users will simply accept, because they either don’t care, don’t understand, or simply don’t have time.

Most apps don’t just keep their data to themselves. There’s a complex arrangement of data sharing that includes advertisers and many other third parties, including major tech companies like Facebook and Google.

Apps are sometimes able to access data even though you may have turned off what seems like the relevant permission. Malicious apps can also subvert the permission system.

In general, if you care about your privacy you should be denying permission to anything that won’t break the app’s core functionality. If an app requires permissions that don’t make sense, let’s say a note-taking app that inexplicably wants access to your camera—it’s a good sign to look for an alternative.

Apps can track you through the resettable advertising ID that you are issued by either Apple or Google. While these are supposed to be anonymous, it is possible to be deanonymized through data from other streams.

Web browser

One of the biggest dangers to privacy is your browsing app, your gateway to the internet. Your browser will be able to access whatever data or resources you have given it permission to access. This can include sensitive things such as your location data, which can be sent back to company servers constantly throughout the day.

The most obvious data is your web activity. Browsers can track and store the details of the sites you visit from day-to-day. Just think about the power of this information—if you are starting to feel unwell, perhaps you would look up the symptoms through your browser. While some people may not care, there are certainly some intimate medical problems that most of us would not want tech companies to know about.

Our browsing history will also often indicate our political leanings, based on the news sites we visit and the articles we view. Of course, your interests will also be revealed, because you probably look up information related to your hobbies all of the time. Searching local restaurants could show where you live. Reviews for certain purchases could reveal data about your income. And this is just the start.

If you use a search engine that is developed by a company separate to your browser, then you will be sending your search queries and clicks to the search provider as well as your browser. To minimize the data provided to third-parties, it’s worth looking into those browsers and search engines that are a little more privacy-focused.

On top of this, the websites you visit can track you as well. Through browser fingerprinting, they can tell what device you use, your configuration, and they may be able to discern your identity. The advertising IDs from Google and Apple can also help them track you across the web. Logging into your accounts can leave behind footprints as you browse the internet.

Unfortunately, there’s even more. Advertisers, ad networks and other third parties can also track you through the likes of JavaScript trackers and cookies. This research paper provides a deep dive into just how pervasive these practices are.

While you are still tracked excessively through your desktop browser, the data collection through mobile browsers is even more worrying because of how much access mobile browsers can have.

Social media & messaging apps

We have already discussed how apps can access whatever you give them permission to. Considering that social media and messaging apps tend to ask for such a wide variety of permissions, it’s a pretty safe bet to assume the worst about their data collection practices.

The likes of Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, and even the relatively young TikTok have all been involved in countless privacy scandals. The bulk of the activity on these platforms is done through their apps, so it’s also a reasonable assumption that this is where most of the data collection occurs.

Facebook tracks people’s locations through the app, your geotagged Tweet history prior to 2015 was available in the API, Instagram tracks a variety of location-related information, while TikTok gets location data through your SIM card, IP address and GPS. These apps have the power to know where you live, where you work, when you go out, and who you spend time with.

Of course, they all get whatever data you give them and post. They also end up with all of the information that your friends post about you as well. They get the contents of your messages too, unless you use end-to-end encryption, such as in WhatsApp. Even when this is the case, these companies can still access the metadata, including who the recipient was, and when the message was sent.

Social media apps may have access to your contacts. Facebook used to have a bug that even made it possible for third-party apps to access photos you hadn’t even posted.

If you have given any of these platforms your phone number for two-factor authentication, it may have even been used for advertising. Both Facebook and Twitter have been fined for this in the past.

Facebook has already settled an Illinois lawsuit regarding its collection of users’ biometric information. The offense was so serious that it cost the company $650 million. Instagram and TikTok are now being sued for the same practice. X — formerly Twitter — changed its privacy policy in September 2023 to allow the collection of biometric data from its users.

It’s not practical to cover all of the different ways that these social media platforms collect your data. However, you can check it out for yourself. You can access your Facebook data by going to the app, clicking on the menu button in the corner, then Settings and Privacy>Settings>Your Facebook Information>Access Your Information>Download Your Information.

In the Instagram app, it’s the menu, then Settings > Security > Data and History > Download Data. On Twitter, you need to log in via the website, click More > Settings and privacy > Select the correct Account under Settings > Then Click on Your Twitter data under Data and permissions.

Through the TikTok app, go to your profile, then click on the ellipses at the top right. Click Privacy and safety > Personalization and data > Download TikTok data.

While you may be shocked by just how much data these companies have on you, at least once you are aware, you can begin taking the steps to minimize their rampant data collection practices.

Virtual assistants

The likes of Siri, Bixby and Google Assistant get a lot of flak from smartphone users. If you talk to your friends or colleagues, you may find that many of them believe these virtual assistants are listening to them, even when the trigger phrase hasn’t been spoken. They may tell you a story about how they were talking about some unusual product, and then the next time they checked their phone, they saw an ad for it. What else could it be, except for their phone spying on their conversation?

While this view is tremendously common, there is no evidence to back it up as a widespread practice. There are plenty of instances where these virtual assistants made recordings when they shouldn’t have, but the most likely reason behind them is that these are just caused by bugs or malfunctions, such as the mishearing of a trigger phrase.

This is because it’s easy for security researchers to look at what data these apps are sending back to the servers. Large amounts of audio voice recordings would not go unnoticed, and we would have plenty of evidence by now.

The most likely explanation for these experiences is a combination of coincidence, plus insights gathered from all of the other data that these companies already have on you. Given the many other streams of data collection that we have discussed so far, plus the complex algorithms, these platforms can make surprisingly accurate predictions.

This isn’t to say that virtual assistant apps don’t collect your data. They certainly do, however, the data they collect is more akin to that of your search engine keeping track of your queries, as opposed to some all-listening, all-knowing deity.

Other apps

If we go through every type of app in detail, this article will quickly become repetitive. Instead, you should be aware that your apps have access to everything you give them permission to, that this can include more data than you may expect, and that it can be shared with third parties like advertisers.

Broadly speaking, apps in these categories will collect the following types of information as well:

- Entertainment apps like YouTube, Netflix and Spotify keep track of what you watch or listen to, for how long you play it, and can make sophisticated profiles and recommendations based on your habits.

- Dating apps like Tinder and Bumble hoover up tremendous amounts of data, including your profile, location, pictures, and any steamy messages you might send to potential matches.

- Map applications like Google Maps can track your location through GPS, cell signal and wi-fi. The latter two still function when the location setting is turned off on a user’s device. They can gather data about your direction, speed, presumed mode of transport and more. Over time, this can build up a profile of your daily activities.

- Email applications like Gmail store all of your sent and received messages, but at least in Gmail’s case, the content is no longer scanned like it used to be. Metadata, which includes who you are talking to and when, is also collected. Gmail can also track your purchases if the receipts are sent through your account.

- Gaming apps can also suck up immense amounts of data and have a tendency to ask for extensive permissions. Angry Birds was even named by the Snowden documents as one of the “leaky” apps that the NSA used to access personal information.

- Finance apps like Acorn and PayPal’s Venmo may be handy, but 80 percent of users don’t realize that these apps store their banking credentials as part of the service they provide.

- Fitness apps like Strava can be great for keeping track of your exercise regimen, but it makes your activities public by default. Sharing information such as where you run or cycle could give away where you live. A 2023 paper by researchers at North Carolina State University said that “the home address of highly active users in remote areas can be identified, violating Strava’s privacy claims and posing as a threat to user privacy”.

- Camera apps like Beauty Plus were found by Trend Micro to be turning on cameras without user permission and spreading malware.

- Rideshare apps like Uber obviously collect data about your trips and analyze them thoroughly. But the geolocation and demand of riders also affects Uber’s surge pricing model.

- Utility apps like system cleaners, antivirus and performance boosters frequently host malware and collect excessive amounts of data.

Other types of apps that we haven’t covered also collect all kinds of data. As we have discussed, even popular apps can have invasive data collection policies. However, you should be wary of lesser-known apps and those that come from developers with poor reputations, because at best these often soak up large amounts of data. At worst, they may be spyware or other types of malware.

Hackers

We’ve covered the bulk of the ways that device manufacturers, operating systems, apps, advertisers and other third parties can track you when you use your smartphone. While some of these may blur legal and ethical boundaries, malicious hackers will jump straight over the line.

Some are motivated by financial gain, often stealing data to sell, or by directly gaining access to bank accounts. Others may be focused on high-value targets such as business executives, government officials or activists. They may be interested in intercepting your communications or stealing sensitive and valuable data.

Less-sophisticated cybercriminals will probably focus on the first tactic, while groups with more resources or links to nation-states may pursue the second line of attack.

Hackers can access your data through a variety of different techniques. Some of the most renowned include:

- Man-in-the-middle attacks – These allow threat actors to insert themselves into your connection, accessing the data that goes in and out of your device. One of the most common MITM attacks involves cybercriminals setting up seemingly legitimate hotspots. They trick users into connecting and then intercept all of the unprotected data that passes through.

- Malicious applications – Threat actors place malware into apps and try to distribute them through app stores. These malicious apps can then spy on users who have been duped into downloading them, track their data and introduce other software into the environment. Apps that seem benign now can introduce malware in a later update.

- Sophisticated malware such as Pegasus – Through phishing and a series of advanced exploits, this type of sophisticated malware can essentially take over the victim’s smartphone.

If hackers manage to put spyware on your device or gain root access, they essentially have free reign over any data that goes in or out of the device. They may be able to find out your passwords and access your accounts, remotely activate your camera and microphone, and even access the content from apps that are generally seen as secure, such as Signal.

If your smartphone gets taken over by hackers, you need to assume that everything on the device could fall into their hands. Even if you get a new device, they may be able to easily gain access through other systems and accounts that they may have already compromised.

The government

The government is another major party that may be able to track you. The specifics will vary from jurisdiction to jurisdiction, with some offering far more protection, transparency and accountability than others.

The types of data collection will vary. In many countries, the authorities will need a warrant to access your smartphone records from your network provider or one of the many tech companies who have data on you. The US has a variety of secret court orders, and even some that don’t involve any judicial oversight. Authoritarian countries and those without due process will likely face similar government overreach.

These types of warrants and orders may give the government access to your past records, or allow them to put you under surveillance. There have also been mass surveillance programs like the NSA’s PRISM and MUSCULAR. While the outrage after the Snowden revelations seems to have scaled such programs back, we can’t know what governments are currently capable of. After all, the NSA’s powers were kept secret for many years.

At a local level, law enforcement may also deploy stingrays, which can force all nearby mobile devices to connect through them. These can identify each device in a given area, track individuals and intercept data.

In addition to these wider surveillance tools, governments may also target individuals. The above-mentioned Pegasus malware is frequently used by governments to get intimate access into the data of journalists, activists and criminals.

How your phone can track you even when turned off

When powered off, smartphones are supposed to be disconnected from cell towers, wi-fi networks, GPS and Bluetooth. However, highly motivated adversaries may be able to continue tracking them when they are off—or at least when they appear to be off.

The FBI listens in to the mafia

While the details are sketchy, the first revelations that phones could be altered to spy even when turned off came in 2006. The news broke out following an FBI investigation into members of a New York organized crime family.

What we know for sure comes from the judge’s opinion. He wrote that the eavesdropping technique “functioned whether the phone was powered on or off”. However, we don’t know exactly how it was accomplished.

The FBI may have gained physical access to the phone and added a separate hardware listening bug to it. If this is the case, then the spying could only be accomplished due to the additional device.

An alternative explanation is that the spying was achieved through software, which may have been planted through a physical or network connection to the device. The CNET article speculated that this was more likely, because the battery of a hardware bug would not have lasted for the whole year of the investigation.

The article also referenced court documents that stated the bug works “anywhere within the United States” and speculated that this would make it outside of the range of an FBI agent with a radio receiver. This also implies that software was the more likely culprit.

The NSA vs Al-Qaeda

One of the next major news stories showing that phones could be tracked even when turned off was published by the Washington Post in 2013. The technique, dubbed, “The Find” gave the NSA thousands of new targets, and was used against an Al-Qaeda sponsored insurgency in Iraq.

The Post did not report on how it worked, but Slate speculated that the devices were infected with malware that could force them to emit signals, unless the battery was taken out. Under normal circumstances, a phone would stop communicating with cell towers when turned off.

Slate’s assumptions seem far more likely than any kind of hardware rig, seeing as the Post implied that the technique allowed the NSA to find the devices, and it would not be practical to physically find the Al-Qaeda phones and insert thousands of listening bugs.

How can phones track you even when they are turned off?

The first possibility involves the attacker planting a hardware spying device on your phone. This would require physical access to your phone for a significant amount of time, which makes these types of attacks unlikely unless you are facing a highly capable threat actor. If your adversary is willing to go to these lengths, it is incredibly difficult for you to maintain your security against them.

If this happened to you and you knew what you were looking for, it may be possible to see the listening device inside the phone if you open it up. However, it is far more likely that your attacker would pursue the easier alternative, through and use malware to spy on you instead.

Under this approach, an attacker could infect your phone over the internet without ever having to go near it. If they did so and then you tried to switch the phone off, it’s possible for the phone to simulate the shutdown process, while still staying active and spying on you.

Note that even when phones indicate that they are out of battery, they aren’t completely drained. You can tell because most phones will display some type of animation to show you that your battery is dead. This would not be possible if it was 100 percent empty. The fact that a small amount of battery remains leaves the possibility open for a phone to transmit signals under certain circumstances.

Can your phone track you when the location is switched off?

Most of us probably don’t have to worry too much about the above scenarios. However, there is a common myth that leads people into a false sense of security.

Many people assume—reasonably so—that they will no longer be physically tracked when they turn off the location setting on their phones. Unfortunately, this is not a case. Switching this setting off does stop you from being tracked by GPS, but that’s just one of the ways that your phone’s location can be recorded:

Network signals

Your cellphone frequently communicates with your network provider’s closest base stations, even when you aren’t making calls. This gives it a rough idea of where your device is.

The strength of your device’s signal, whether it is stronger or weaker, gives your provider even more information about how far away your cell phone is from a tower. When the signal from multiple towers is combined, it’s possible to narrow down the location even further.

The accuracy varies according to the technique used and the density of base stations in an area. In some urban areas, it’s possible to pinpoint a device’s location to within 50 to 100 meters with Advanced Forward-Link Trilateration. It can be significantly less accurate in rural regions, due to the lower concentration of cell towers.

Network providers often hand over this data to the authorities, and have even been known to sell it as well. When this data was placed on the market, a range of people could purchase it with limited oversight, granting them knowledge of a phone’s location within a few hundred meters.

It’s not just your network provider who has access to this type of location information. Google was caught collecting data about the closest towers from phones that didn’t even have SIM cards. While the company promised to end the practice, the immense complication of our communication systems and the unscrupulous behavior from the companies involved shows just how difficult it is to prevent ourselves from being tracked.

Wi-fi

Just as your network provider can gauge your location based on where you are in relation to its towers, wi-fi access points also give away where you are. If wi-fi is turned on, your operating system can periodically send the wi-fi access point’s service set identifier (SSID) and media access control (MAC) address to companies like Google. This gives them a rough idea of your location.

Free wi-fi providers are also renowned for invasive tracking, because they can link these identifiers to whatever personal information you provide when you sign in to the service.

When wi-fi is turned on, phones send out data when searching for access to points to connect to. They don’t even have to connect for this data to be sent out to access points, or to any hackers that may be intercepting this data as well.

Bluetooth

Bluetooth doesn’t keep track of the physical location in space like GPS does, but it does record interactions with other Bluetooth devices. However, if your phone’s Bluetooth is recognized by a store’s Bluetooth beacon—or someone else’ device whose location was known—this infers that your device was in the same place at that particular time.

This makes it possible to track your device through Bluetooth. We see this in the promotions stores send to their customers via push notifications when their Bluetooth comes within range. Countries all over the world are also using Bluetooth interactions to track the spread of coronavirus.

While you may have thought that turning off your Bluetooth would completely stop this from happening, it isn’t always the case. In 2018, Quartz found that Android devices could still be tracked through Bluetooth beacons while Bluetooth was turned off. However, this was only possible if the device had the app for a nearby store installed.

Other possible tracking mechanisms

If all of these techniques haven’t scared you enough, a paper published by the Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers may do the trick. A team of academics created an experimental app that could track users through other means, such as the device’s timezone, its gyroscope, accelerometer, barometer and magnetometer.

According to the paper, these sensors can be accessed without a user’s permission, and could be used to ‘accurately estimate the user’s location. Although we have no confirmations that any companies use similar techniques to track users, this proof-of-concept of even more ways to track us should be worrying enough.

How can you fight mobile data tracking?

The ideal solution is probably to find the nearest river and heft your smartphone into its murky depths. Most smartphones are absolutely terrible for your privacy. Those that aren’t, such as the Librem 5, are generally lacking in features or functionality. It comes down to the way that smartphone ecosystems are designed, they’re just bad for privacy, far worse than computers.

But few of us are going to give up the convenience and connection that our smartphones offer us and go off and live in the woods. For most of us, smartphones have become essential parts of our professional and social lives, and completely giving them up would be immensely challenging.

So what choice do we have?

It’s probably going to take a long time before most of the world has any reasonable regulatory protections against the privacy invasions of smartphones, so your only realistic option is to take your own steps toward preserving your privacy.

Here’s how to fight mobile data tracking:

- Minimize your smartphone use

- Use a privacy-focused phone or operating system

- Use privacy-focused apps

- Limit ad tracking and reset your advertising ID

- Use a VPN

- Lock down the settings on all of your accounts

We’ll go into more detail on each of these precautions below.

1. Minimize your smartphone use

To start with, avoid smartphones as much as realistically possible. If you can get by with just a dumbphone and a computer, do that. Make people call or text you for emergencies, and deal with everything else when you are at your computer.

If a smartphone is a must, leave it at home when you don’t need it. Keep the number of apps on it to a minimum, and limit the amount of data that it has access to. If you must have access to social media on your phone, try to access the sites through your mobile browser rather than having the apps installed on your device.

For any apps that you do have, limit the permissions for what they can access to the bare minimum. Keeping data, wi-fi, Bluetooth and location switched off when you aren’t using them may also help.

2. Use a privacy-focused phone or operating system

Phones such as the Librem 5 are designed with privacy in mind, so they are a good choice if you really want to limit data collection. However, these are relatively small companies with neither the research and development budgets, nor the economies of scale that their mainstream rivals have. While these privacy-focused companies are generally doing good work, these limitations tend to result in phones that are less sleek, limited in features and more expensive than their competitors.

Another good option is to get a compatible Android phone and set it up with a privacy-focused operating system like LineageOS, instead of Android with Google Mobile Services. This will require a lot more effort to set up than a normal phone, and is probably only a suitable option for those who are more technical.

Realistically, the vast majority of people aren’t going to find the above two options suitable, so the next best option is an iPhone. If you are a diehard Android supporter or simply find iPhones too expensive, you can still limit the data collection through your Android device by following the rest of these steps.

3. Use privacy-focused apps

The good news it that there are a number of apps that protect your privacy much more than the ones you may be used to:

- Use Firefox or the Tor browser instead of Google Chrome or Safari. Note that there is no official Tor browser on iOS, but the Tor Project does encourage Onion Browser. Use DuckDuckGo or Startpage as your search engine. If you use Firefox as your browser, you can lock it down even further with add-ons like uBlock Origin, HTTPS Everywhere, NoScript, and Decentraleyes.

- Use Signal as your messaging app. Failing that, WhatsApp or Telegram are better than Facebook Messenger and Instagram.

- Use a maps tool like MAPS.ME instead of Google Maps.

- Use NewPipe instead of YouTube.

There are many more apps that offer better privacy options than those that you may be accustomed to. Privacytools.io and PRISM BREAK both have a number of good recommendations. Alternatively, you may want to look into some of the free and open-source software (FOSS) alternatives.

4. Limit ad tracking and reset your advertising ID

On Android, you can limit ad tracking by going into Settings, then selecting Google, then clicking on Ads. From this menu, you can click to Reset your advertising ID, and slide the toggle for Opt out of Ads Personalization.

On iOS, you can do the same by going to Settings, then Privacy, to Advertising, and then clicking on Limit Ad Tracking. There is also an option to Reset your advertising identifier.

5. Use a VPN

VPNs can help to hide your identity by obscuring where your traffic originates from. However, you still have to be careful about how you use them. If your VPN gets cut off and there is no killswitch to stop the connection, your IP address might be revealed. While VPNs are great for protecting your data from your ISP, they can’t stop you being identified by websites through browser fingerprinting. Logging in and entering your personal details will also give you away.

Use a reputable company that ideally takes no logs, such as one from our best VPNs list. Be wary of free VPNs, because they may sell your data or include malware.

6. Lock down the settings on all of your accounts

In response to Europe’s landmark General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) introduced in 2018, companies began introducing more granular privacy settings that gave users back at least some control of their data. All of the tech giants have these, including Facebook, Google, Amazon, Twitter, Microsoft, and the many other companies that store your data.

While these tools can be confusing and don’t allow you to limit all types of data collection, they can help to significantly cut back on the amount of data that these companies keep on you. They are usually found in the privacy settings of the respective app or website.

The future of smartphone tracking

All of the above recommendations are just a start. They won’t make your smartphone invisible to the outside world, but they will significantly cut back on the amount of data collected from your device.

Unless we are willing to go to the extreme lengths of completely giving up our smartphones or dedicating significant amounts of our time to OpSec, we are going to have to accept that we will be tracked to some degree well into the future.

Due to the complexity of these systems, and the fact that most of us simply don’t have the time to understand them and navigate them effectively, it seems like the only possible savior will be regulation. We need laws that simplify these systems, make everything easier to understand, offer meaningful ways to opt-out, ban the most egregious forms of tracking and severely penalize offenders.

At the moment, such laws seem like pipe dreams for the majority of the world. For now, you will have to take things into your own hands if you want to limit the tracking as much as possible.

See also: